From 1990 on, and almost until the end of its presence in Germany, the 16.VA continued somehow

to train its pilots despite the reductions imposed on military operations in the C.I.S. by the lack of funds and

limitations of flights requested by the German Government. The latter consisted mainly in a drastic reduction or complete

cessation of supersonic flights, the use of firing ranges and air space. When combined, these limitations prevented

the organization of complex tactical scenarios or even simple air-to-air exercises.

The central air operations command post of the ZGV at Wünsdorf had to accomodate, from April 1990 on, with a German

"stepmother" responsible for air security, the LUKO (Luftraum-Koordinierungsstelle - Airspace coordination section).

It was a Luftwaffe liaison and coordination unit monitoring all flights of Russian combat aircraft -

aircraft and helicopters alike - in the heavens of the "Ehemalige DDR". This service was controlling that the

flying rules issued by the Bonn authorities were respected.

From 1990 on, and almost until the end of its presence in Germany, the 16.VA continued somehow

to train its pilots despite the reductions imposed on military operations in the C.I.S. by the lack of funds and

limitations of flights requested by the German Government. The latter consisted mainly in a drastic reduction or complete

cessation of supersonic flights, the use of firing ranges and air space. When combined, these limitations prevented

the organization of complex tactical scenarios or even simple air-to-air exercises.

The central air operations command post of the ZGV at Wünsdorf had to accomodate, from April 1990 on, with a German

"stepmother" responsible for air security, the LUKO (Luftraum-Koordinierungsstelle - Airspace coordination section).

It was a Luftwaffe liaison and coordination unit monitoring all flights of Russian combat aircraft -

aircraft and helicopters alike - in the heavens of the "Ehemalige DDR". This service was controlling that the

flying rules issued by the Bonn authorities were respected.

After the fall of the USSR, no more than fifty hours of flight training per year and per pilot were conducted on average,

a situation that had obviously an adverse effect on the operational level of the pilots. That meant for most Russian

aircrew just two half an hour flights per working week. However, records of the LUKO showed between 1990 and April 1994

(1), a total of 271,231 aircraft flights and 245,673 helicopter flights

(2). Although aviation activity remained intense

as far as the number of movements recorded between 1990 and 1991 are concerned, the dissolution of the USSR and the gradual departure of units

from Germany led to a sharp decline in flight activities from 1992 on (3).

After the fall of the USSR, no more than fifty hours of flight training per year and per pilot were conducted on average,

a situation that had obviously an adverse effect on the operational level of the pilots. That meant for most Russian

aircrew just two half an hour flights per working week. However, records of the LUKO showed between 1990 and April 1994

(1), a total of 271,231 aircraft flights and 245,673 helicopter flights

(2). Although aviation activity remained intense

as far as the number of movements recorded between 1990 and 1991 are concerned, the dissolution of the USSR and the gradual departure of units

from Germany led to a sharp decline in flight activities from 1992 on (3).

Before the fall of the Iron Curtain planes and helicopters of the ZGV flew without real economic, political

or environmental constraints, but from 1992 on and until their closure, the airbases of the VVS in reunified Germany

became active only one, or two days per week and for a limited number of hours only.

The operating hours depended in general

of the season: from 9 to 18 hours in summer and from 15 to 21 hours in winter (primarily for flight training at night).

Sometimes if the weather was too bad or if an unforeseen event occurred the Friday served as a reserve day.

A typical day of operation on a Russian airbase in Germany differed fundamentally from its counterpart on the

NATO side. It took place in a ritual almost immutable, summer like winter. Approximately two hours before the start of flights,

the aircraft were towed by truck from their armored shelters and brought on a flightline.

The operating hours depended in general

of the season: from 9 to 18 hours in summer and from 15 to 21 hours in winter (primarily for flight training at night).

Sometimes if the weather was too bad or if an unforeseen event occurred the Friday served as a reserve day.

A typical day of operation on a Russian airbase in Germany differed fundamentally from its counterpart on the

NATO side. It took place in a ritual almost immutable, summer like winter. Approximately two hours before the start of flights,

the aircraft were towed by truck from their armored shelters and brought on a flightline.

|

|

That long platform, often parallel and close to the runway, was able to accommodate simultaneously up to a complete regiment.

It was equipped with fixed jet blast deflectors, high lighting masts, compressors riveted to the ground and kerosene refueling

pumps feeded by underground pipes. Around one hour before the beginning of flying operations, a two-seater weather

reconnaissance aircraft took off. In the G.D.R., the weather flights were most of the time conducted by the ubiquitous

MiG-23UB "Flogger-C".

After fifteen minutes the aircraft returned to base and its crew reported. If the weather situation in the scheduled training

area was within the minimum requirements, the missions began within the hour. Meanwhile, pilots and mechanics received their

final instructions before joining the flightline on foot or by bycicle.

After the traditional pre-flight checks, pilots quickly cimbed aboard their aircraft, and as soon as attached to

their seat, started the engine(s).

That long platform, often parallel and close to the runway, was able to accommodate simultaneously up to a complete regiment.

It was equipped with fixed jet blast deflectors, high lighting masts, compressors riveted to the ground and kerosene refueling

pumps feeded by underground pipes. Around one hour before the beginning of flying operations, a two-seater weather

reconnaissance aircraft took off. In the G.D.R., the weather flights were most of the time conducted by the ubiquitous

MiG-23UB "Flogger-C".

After fifteen minutes the aircraft returned to base and its crew reported. If the weather situation in the scheduled training

area was within the minimum requirements, the missions began within the hour. Meanwhile, pilots and mechanics received their

final instructions before joining the flightline on foot or by bycicle.

After the traditional pre-flight checks, pilots quickly cimbed aboard their aircraft, and as soon as attached to

their seat, started the engine(s).

Les risques du métier! Une roquette a explosé lors de sa mise à feu, éventrant le panier

B-8M1 de ce Su-17. © 20.GvAPIB

Les risques du métier! Une roquette a explosé lors de sa mise à feu, éventrant le panier

B-8M1 de ce Su-17. © 20.GvAPIB

Risky business! A rocket has exploded inside the B-8M1

pod of this Su-17. © 20.GvAPIB

Une para de Su-17 tire une salve de roquettes S-5 sur une cible du polygone de tir

de Wittstock. © 20.GvAPIB

Une para de Su-17 tire une salve de roquettes S-5 sur une cible du polygone de tir

de Wittstock. © 20.GvAPIB

Two Su-17 from Gross Dölln shooting unguided S-5

rockets on a target at the Wittstock range. © 20.GvAPIB

After a quick high power engine test, they taxied to the runway and took off immediately.

The flight scheme was very rigid. Right after take off, the pilot took the direction of the exercise area where, after

a few target attacks or maneuvers, they immediately set course towards their base. The landing was performed after a long flat

approach which was rarely followed by a touch and go. Quality as the average wear of the tyres probably explained

the rarity of such a maneuver. Training missions were very short and rarely exceeded twenty to thirty minutes, even for

long-range aircraft like the Su-24 "Fencer". During the flying hours, activity was intense. The missions followed in

rapid succession. No sooner landed, aircraft were quickly prepared for the next mission and it was not rare to count

more than six sorties per aircraft. The number of missions was progressively decreasing when the end of the flying

activities approached.

In winter, a procedure developed by the VVS during the Second World War

was applied for night landings. The airbases were equipped with a very limited lighting system. Instead, a clever and efficient

technique had been developed. Four trucks equipped with large searchlights were positioned slightly before the beginning of the runway

and at the threshold itself. When an aircraft approached, these lights were suddenly switched on, piercing the night over

a distance of about 200 or 300 meters in the direction of landing.

In winter, a procedure developed by the VVS during the Second World War

was applied for night landings. The airbases were equipped with a very limited lighting system. Instead, a clever and efficient

technique had been developed. Four trucks equipped with large searchlights were positioned slightly before the beginning of the runway

and at the threshold itself. When an aircraft approached, these lights were suddenly switched on, piercing the night over

a distance of about 200 or 300 meters in the direction of landing.

As soon as the aircraft had landed, the searchlights were switched off. Needless to say that this landing procedure

offered truly magical visions. One must have heard and then suddenly saw emerge from the darkness like grey ghosts

the Su-24 "Fencer" of Welzow, to appreciate the magic of these brief night illuminations

(see > Night Flight).

As soon as the aircraft had landed, the searchlights were switched off. Needless to say that this landing procedure

offered truly magical visions. One must have heard and then suddenly saw emerge from the darkness like grey ghosts

the Su-24 "Fencer" of Welzow, to appreciate the magic of these brief night illuminations

(see > Night Flight).

While most of the Russian bases in Germany except those of Brand, Gross Dölln and Welzow had only a single paved runway,

they were all systematically equipped with additional or emergency tracks constituted by the long taxiways, platforms and

stabilized grass bands parallel to the main runway. In case of alert evacuation, all the aircraft of the regiment

(or around forty aircraft) could take off in fifteen minutes using a procedure that would have made the hairs of a western

security officer stand on his head.

Posés sur une borne de ravitaillement en carburant,

des parachutes de freinage attendent, parés pour le prochain vol.

© H.Mambour

Posés sur une borne de ravitaillement en carburant,

des parachutes de freinage attendent, parés pour le prochain vol.

© H.Mambour

Brake chute packs ready for the next flight, resting on a

fixed refuelling station. © H.Mambour

For that purpose, the aircraft were taking off by Zveno (four aircraft) from the two

ends of the runway, each in turn. Two aircraft took off from the main runway, one from a parallel taxiway and one from

the grass band, all at the same time. The maneuver took about one minute and twenty seconds per patrol.

Immediately after, the next Zveno aligned on the other end of the airfield and took off in the

opposite direction.

Another procedure was to

align 2 to 4 aircraft - depending on the width of the runway - at each end and let each group of aircraft take off

alternately in opposite directions. The following aircraft were waiting on the taxiway or on a standby area situated

next to the runway threshold on the taxiway side, ready to enter the runway as soon as the preceding aircraft had took off.

Such a scene can be very briefly observed on a film made at Gross Dölln in 1991

(see > Multimedia & links)

(4).

Un pilote du 787.IAP monte à bord de son MiG-29 orné du badge otlitchniy samolet qui indique une machine

particulièrement fiable. © P.Bigel

Un pilote du 787.IAP monte à bord de son MiG-29 orné du badge otlitchniy samolet qui indique une machine

particulièrement fiable. © P.Bigel

A pilot of the 787.IAP

climbs aboard its MiG-29 decorated with a otlichniy samolet badge,

which indicates a very reliable airplane. © P.Bigel

The general "decaying" or basic aspect of Soviet military installations was always drawing the

attention of the lambda Western observer. For exemple, the sliding door rails of some models of hardened aircraft shelters

(as seen at Preschen, a former basis of the LSK/LV) were not embedded in concrete,

but riveted over it. Consequently, the aircraft had to cross that obstacle when entering or exiting their HAS.

But it would have been unwise to draw a conclusion based on such details.

A German officer questioned about this by a friend said essentially this: "Do not be fooled by appearances, for the

Russians outward appearance does not count and all that is essential to the accomplishment of the missions is achieved. This is

not made to be beautiful or clean, it is made for war." A word to the wise is enough.

Une cordelette scellée par des cachets de cire condamne la porte latérale de ce Mi-8.

© H.Mambour

Une cordelette scellée par des cachets de cire condamne la porte latérale de ce Mi-8.

© H.Mambour

Wax seals were used to condemn aircraft and also

building or office doors. © H.Mambour

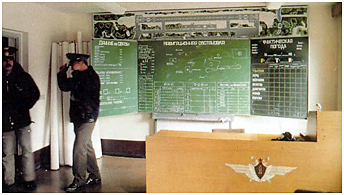

La salle de briefing de Gross Dölln. Au-dessus du tableau noir, on distingue une représentation

de la piste et des taxiways. La seconde piste, inutilisée, ne figure pas sur le plan. © 20GvAPIB

La salle de briefing de Gross Dölln. Au-dessus du tableau noir, on distingue une représentation

de la piste et des taxiways. La seconde piste, inutilisée, ne figure pas sur le plan. © 20GvAPIB

Gross Dölln briefing room. A runway and taxiways plan can be seen above the blackboard.

The unused second runway is not shown. © 20GvAPIB

Finally, another habit never failed to amaze the Western visitor. To protect their offices, buildings and even

doors and some access panels for their aircraft, the Russians used a system of delicate old-fashioned:

wax seals.

Disappeared from our regions for the benefit of locks and padlocks often as thick as the psychology of their users,

small wax seals marked with the stamps of the responsible persons, stand up as cheap and effective security barriers.

Barriers certainly more dissuasive than the metal gates and tire bursting traps that closed the taxiways when there was

no flying activity. If some disgruntled people have considered this anti-intrusion protections as a means to avoid

defection of pilots with their aircraft, we are compelled to note - most of the aircraft of the VVS were

able to operate from grass runways - that this explanation is unlikely and this irrespective of the degree of

paranoia developed by the Soviet communist system at the time of its splendor.

notes

(1)

The LUKO was officially disbanded on April 29, 1994. However, it continued to operate until the departure of

the last Russian military aircraft from Germany.

(2)

These figures seem exaggerated at first sight, but they must be considered in a correct context. During our first week

spent in former G.D.R. before the end of the Soviet Union, we observed no less than seven active bases.

With a pessimistic estimation of 12 aircraft flying per base (84 aircraft in total) and three missions per aircraft,

we get 252 movements. There is no doubt that other bases were active during that week.

Probably at least 3, perhaps up to six. This brings the total of movements for this week in a

range between 360 and 576! And perhaps are we still well below the reality ...

(3)

According to General Tarasenko himself, the restrictions have prevented the 16.VA flight training at night during

4 months in 1991 and six months (from April 15 to October 15) in 1992. The training during daytime was to be completed before

18H00, on average two hours before sunset. Consequently, the organization of missions was left to the

discretion of the regimental commanders to allow younger pilots and crews "war ready" -

these two groups representing the present and the future force of the VVS - to achieve the greatest number of flying hours. In order

to adapt

to the flight restrictions and unfavorable economic conditions, the duration of the missions was reduced, and the passes

over the ranges were reduced to a single one per aircraft, whereas more complex missions scenarios were preferred.

The use of afterburner (except on take-off) and flight in really bad weather conditions

were banned to save fuel. Flight simulators were privileged despite their lack of sophistication. In fact,

flight training was based on the available fuel rather than on operational requirements. The restrictions imposed by

the German Government were partly offset by the periodic

deployment (without the planes?) of units in Russia for shooting campaigns lasting one week. They accounted for

37% of the total of the 16.VA flight hours, including 50% of night flying hours in 1992. ( "Comments on

the problems of the 16th Air Army in Krasnaya Zvezda)

(4)

A somewhat similar procedure was observed by USMLM at Altenburg on 16 March 1973. On that day, 15 MiG-21MT/SMT of the local

régiment scrambled in 11 minutes. The first nine aircraft took off to the southwest, with the remaining six taking off

to the northeast. See > Altenburg Squadron "Flush".

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |