Following the article "Safety of Flignt Not Garanteed" describing the BRIXMIS observation flights over the BCZ, we continue the study of this subject thanks to Squadron Leader Tony Bowen, a former Victor pilot, who was the last pilot to fly the Chipmunk in Berlin during operation Nylon/Schooner/Oberon.

He tells us about his service at RAF Gatow and over the Berlin Control Zone.

On 20 June 1990 I set off with my wife and our daughter from Thirsk, North Yorkshire, at the start of a 900 mile journey into the unknown. We did actually

know where we were going - Berlin - but even I did not really know why. I was aware that my job title was Public Relations Officer/Chipmunk QFI and I'd had a hint

that there might be something different about the flying but that I would be told more when I arrived. Intriguing! Eventually we arrived at the frontier between

West and East Germany in the town of Helmstedt and reported to Checkpoint Alpha (> Link). Here I was given 2 things: a

time slot and a laminated sheet of paper. There was a national speed limit of 100 kph in the DDR which was strictly enforced. The time slot was my allocated arrival

time at the border with West Berlin Checkpoint Bravo (> Link) and allowed a tolerance of plus or minus 10 minutes.

Any earlier and I must have been speeding, any later and it was obvious that I had stopped for a bit of spying! By now you've probably deduced that the border between West and East

Berlin was... Checkpoint Charlie! (> Link) The paper was for me to hand to any Volkspolizei officer who might stop

me and in German, Russian and English said in effect: "I am not permitted to speak to you please take me to the nearest Soviet officer." I was to see this paper again but

more of that later. Finally, after a journey of some 18 hours, we arrived at RAF Gatow.

On 20 June 1990 I set off with my wife and our daughter from Thirsk, North Yorkshire, at the start of a 900 mile journey into the unknown. We did actually

know where we were going - Berlin - but even I did not really know why. I was aware that my job title was Public Relations Officer/Chipmunk QFI and I'd had a hint

that there might be something different about the flying but that I would be told more when I arrived. Intriguing! Eventually we arrived at the frontier between

West and East Germany in the town of Helmstedt and reported to Checkpoint Alpha (> Link). Here I was given 2 things: a

time slot and a laminated sheet of paper. There was a national speed limit of 100 kph in the DDR which was strictly enforced. The time slot was my allocated arrival

time at the border with West Berlin Checkpoint Bravo (> Link) and allowed a tolerance of plus or minus 10 minutes.

Any earlier and I must have been speeding, any later and it was obvious that I had stopped for a bit of spying! By now you've probably deduced that the border between West and East

Berlin was... Checkpoint Charlie! (> Link) The paper was for me to hand to any Volkspolizei officer who might stop

me and in German, Russian and English said in effect: "I am not permitted to speak to you please take me to the nearest Soviet officer." I was to see this paper again but

more of that later. Finally, after a journey of some 18 hours, we arrived at RAF Gatow.

BRIXMIS

In 1946 a unit was formed within the DDR entitled the British Commanders' in Chiefs Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany or simply by the acronym BRIXMIS. There were

similar missions for the French (FMLM), Americans (USMLM) and Soviets (SOXMIS). All the charters were slightly different; the British was as shown here

> Link.

The agreements allowed for a number of members of each mission to be issued with a pass giving them access to each other's zone of occupation. According to the chronology of the creation of the missions, the British obtained 31 passes, the French 18 and the Americans 14. The first BRIXMIS Mission House was actually a group of 4 houses in a small close just off the main

Geschwister-Scholl-Srasse in Potsdam, but, following some significant damage caused during an anti-British demonstration, the Soviets agreed to pay compensation of

£1200 in "crisp white fivers" and to provide a new Mission House on Seestrasse, Potsdam. Although originally intended as a communications channel, it was soon realised

that BRIXMIS provided an opportunity to observe Soviet Forces in the forward operating area. Accordingly the unit contained a large number of highly specialised soldiers and

airmen who were able to evaluate the Soviet and East German Forces which would, in the event of war, be in the vanguard of any assault on the Inner German Border. The unit employed

a number of vehicles which evolved over the years until they eventually settled on the Mercedes Geländewagen, known affectionately as the "G Wagon." It was an excellent

cross-country vehicle which provided good accommodation for a crew of 3. When fully equipped the BRIXMIS fleet contained an impressive array of vehicles.

The standard ground tour lasted between 3 and 5 days during which the crew lived, ate and slept with their vehicle. The driver also had to sleep in the vehicle while the other 2

often slept in bivouacs close by. RAF officers and SNCOs wondered why they had been instructed to take flying kit with them. After some 3 months or so they found out when they were

told to report to RAF Gatow (> History) where, for the first time they learned all about Operation Nylon or Schooner. Such was the secrecy

that surrounded this operation that they found themselves in much the same situation as I arrived at in June 1990.

In 1946 a unit was formed within the DDR entitled the British Commanders' in Chiefs Mission to the Soviet Forces in Germany or simply by the acronym BRIXMIS. There were

similar missions for the French (FMLM), Americans (USMLM) and Soviets (SOXMIS). All the charters were slightly different; the British was as shown here

> Link.

The agreements allowed for a number of members of each mission to be issued with a pass giving them access to each other's zone of occupation. According to the chronology of the creation of the missions, the British obtained 31 passes, the French 18 and the Americans 14. The first BRIXMIS Mission House was actually a group of 4 houses in a small close just off the main

Geschwister-Scholl-Srasse in Potsdam, but, following some significant damage caused during an anti-British demonstration, the Soviets agreed to pay compensation of

£1200 in "crisp white fivers" and to provide a new Mission House on Seestrasse, Potsdam. Although originally intended as a communications channel, it was soon realised

that BRIXMIS provided an opportunity to observe Soviet Forces in the forward operating area. Accordingly the unit contained a large number of highly specialised soldiers and

airmen who were able to evaluate the Soviet and East German Forces which would, in the event of war, be in the vanguard of any assault on the Inner German Border. The unit employed

a number of vehicles which evolved over the years until they eventually settled on the Mercedes Geländewagen, known affectionately as the "G Wagon." It was an excellent

cross-country vehicle which provided good accommodation for a crew of 3. When fully equipped the BRIXMIS fleet contained an impressive array of vehicles.

The standard ground tour lasted between 3 and 5 days during which the crew lived, ate and slept with their vehicle. The driver also had to sleep in the vehicle while the other 2

often slept in bivouacs close by. RAF officers and SNCOs wondered why they had been instructed to take flying kit with them. After some 3 months or so they found out when they were

told to report to RAF Gatow (> History) where, for the first time they learned all about Operation Nylon or Schooner. Such was the secrecy

that surrounded this operation that they found themselves in much the same situation as I arrived at in June 1990.

The station was home to 2 Chipmunk T.10 training aircraft which had been given dispensation under the 1947 Quadripartite Air Agreement to operate within the Berlin Control Zone in order that pilots and aircrew could maintain their flying skills. Very early on it was realised that, although the zone only covered a 20 mile radius, it still included a large area which accommodated many Soviet and East German army and airforce units. The little Chipmunk provided an unparalled viewing platform from which to observe and photograph a lot of hardware, much of which was seen for the first time by the western Allies. So, I was driven by my predecessor, Sqn Ldr Mike Miall, up to the hangar where the aircraft were housed. We went down into the basement where we changed into flying kit and I was handed a laminated sheet of paper. This was the same paper that I had seen previously at Checkpoint Alpha on my drive to Berlin and meant that, in the event of a forced landing in the DDR, I should be taken to the nearest Soviet officer. It was expected that this would be the prelude to what was known colloquially as "the long Russian course".

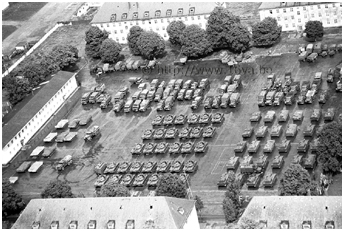

Once we were seated in the aircraft, helmets on and dark visors lowered, the hangar doors were opened and we were pushed out into the open to start the engine. Then came the radio call: "Zenith Alpha, taxy" followed a short time later at the end of the runway by: "Zenith Alpha, ready for departure." Cleared for take-off, there followed the strangest one hour 40 minutes of my life during which we traversed some 150 miles around a major city, in and out of the traffic patterns of Tempelhof and the East German civilian airport of Schönefeld, the helicopter base at Oranienburg and the reconnaissance base at Werneuchen - all without a single R/T transmission. Eventually, one final call some 3 miles from Gatow: "Zenith Alpha field in sight." "Zenith Alpha cleared to land." Safely back on terra firma the earlier procedure was reversed as the engine was shut down, hangar doors opened, aircraft pushed in, doors closed and we were finally able to remove our helmets and climb out. And the reason for this apparent pantomime? Just outside the airfield boundary there was a watchtower manned by East German Border Guards from which all our movements were observed and photographed in an attempt to identify the aircrew.

The station was home to 2 Chipmunk T.10 training aircraft which had been given dispensation under the 1947 Quadripartite Air Agreement to operate within the Berlin Control Zone in order that pilots and aircrew could maintain their flying skills. Very early on it was realised that, although the zone only covered a 20 mile radius, it still included a large area which accommodated many Soviet and East German army and airforce units. The little Chipmunk provided an unparalled viewing platform from which to observe and photograph a lot of hardware, much of which was seen for the first time by the western Allies. So, I was driven by my predecessor, Sqn Ldr Mike Miall, up to the hangar where the aircraft were housed. We went down into the basement where we changed into flying kit and I was handed a laminated sheet of paper. This was the same paper that I had seen previously at Checkpoint Alpha on my drive to Berlin and meant that, in the event of a forced landing in the DDR, I should be taken to the nearest Soviet officer. It was expected that this would be the prelude to what was known colloquially as "the long Russian course".

Once we were seated in the aircraft, helmets on and dark visors lowered, the hangar doors were opened and we were pushed out into the open to start the engine. Then came the radio call: "Zenith Alpha, taxy" followed a short time later at the end of the runway by: "Zenith Alpha, ready for departure." Cleared for take-off, there followed the strangest one hour 40 minutes of my life during which we traversed some 150 miles around a major city, in and out of the traffic patterns of Tempelhof and the East German civilian airport of Schönefeld, the helicopter base at Oranienburg and the reconnaissance base at Werneuchen - all without a single R/T transmission. Eventually, one final call some 3 miles from Gatow: "Zenith Alpha field in sight." "Zenith Alpha cleared to land." Safely back on terra firma the earlier procedure was reversed as the engine was shut down, hangar doors opened, aircraft pushed in, doors closed and we were finally able to remove our helmets and climb out. And the reason for this apparent pantomime? Just outside the airfield boundary there was a watchtower manned by East German Border Guards from which all our movements were observed and photographed in an attempt to identify the aircrew.

Back in 1966 when I was a co-pilot on the Victor B.2 bomber equipped with the Blue Steel stand-off nuclear missile, my sole mission was to prepare to launch an attack on the Soviet Union which would obliterate a city of some 200,000 inhabitants - roughly the size of Plymouth. My security clearance at that time was lower than that required for me to fly my humble Chipmunk in Berlin.

All RAF flights had to be authorised in writing before flight with details of their purpose but in Berlin all that was entered (and indeed recorded in my personal logbook) was "local flying". It was only when researching this article that I even knew that our flights were given the codenames of Operation Nylon, Schooner and later Oberon. The whole undertaking was so sensitive that it was subject to Cabinet Office approval to the extent that, during General Elections, flights were suspended pending any possible change of government. In 1990, if I had inadvertently let slip any hint of what I was doing I'd have had to shoot you!

Time here for a slight digression. When I went to Berlin I had just 2 weeks with Mike Miall to carry out a handover before I had to go down to Rheindahlen for a colloquial German course. By the time that finished Mike would be on his way back to the UK. No problem as he explained that we would concentrate exclusively on the flying side leaving his very capable deputy, Werner Muths, to guide me through the PR side of the job. When I got back to Gatow, Werner was on leave but due back the following Monday. On my first Friday in the office the door opened and in came the RAF Police squadron leader accompanied by 2 civilians. I was asked to confirm that Herr Muths would be back from leave on Monday and when I did so I was told: "At 9 o'clock your door will open and these 2 gentlemen will come in. Nothing will be said and you will just get up, leave and come upstairs to the police office where you will stay until we say you can return." They would not tell me anything else but on the Monday morning, at 9 o'clock precisely the door duly opened and in came the same 2 gentlemen accompanied by a lady. I duly did as I had been instructed and remained in the police office for some 3 hours. When I was allowed to return to my office it was empty. It transpired that Werner Muths, who had worked at Gatow for some 15 years, first as deputy manager of the Officers' Mess and then as deputy PRO, was actually a STASI agent! So all this subterfuge about shielding our identities was a complete waste of time! On a personal level I was instantly deprived of all the PR knowledge on which I was to rely leaving me at the foot of a pretty steep learning curve.

Back in 1966 when I was a co-pilot on the Victor B.2 bomber equipped with the Blue Steel stand-off nuclear missile, my sole mission was to prepare to launch an attack on the Soviet Union which would obliterate a city of some 200,000 inhabitants - roughly the size of Plymouth. My security clearance at that time was lower than that required for me to fly my humble Chipmunk in Berlin.

All RAF flights had to be authorised in writing before flight with details of their purpose but in Berlin all that was entered (and indeed recorded in my personal logbook) was "local flying". It was only when researching this article that I even knew that our flights were given the codenames of Operation Nylon, Schooner and later Oberon. The whole undertaking was so sensitive that it was subject to Cabinet Office approval to the extent that, during General Elections, flights were suspended pending any possible change of government. In 1990, if I had inadvertently let slip any hint of what I was doing I'd have had to shoot you!

Time here for a slight digression. When I went to Berlin I had just 2 weeks with Mike Miall to carry out a handover before I had to go down to Rheindahlen for a colloquial German course. By the time that finished Mike would be on his way back to the UK. No problem as he explained that we would concentrate exclusively on the flying side leaving his very capable deputy, Werner Muths, to guide me through the PR side of the job. When I got back to Gatow, Werner was on leave but due back the following Monday. On my first Friday in the office the door opened and in came the RAF Police squadron leader accompanied by 2 civilians. I was asked to confirm that Herr Muths would be back from leave on Monday and when I did so I was told: "At 9 o'clock your door will open and these 2 gentlemen will come in. Nothing will be said and you will just get up, leave and come upstairs to the police office where you will stay until we say you can return." They would not tell me anything else but on the Monday morning, at 9 o'clock precisely the door duly opened and in came the same 2 gentlemen accompanied by a lady. I duly did as I had been instructed and remained in the police office for some 3 hours. When I was allowed to return to my office it was empty. It transpired that Werner Muths, who had worked at Gatow for some 15 years, first as deputy manager of the Officers' Mess and then as deputy PRO, was actually a STASI agent! So all this subterfuge about shielding our identities was a complete waste of time! On a personal level I was instantly deprived of all the PR knowledge on which I was to rely leaving me at the foot of a pretty steep learning curve.

So, let's look at a typical sortie. On the morning of a planned BRIXMIS flight a specialist officer or SNCO would drive down to Gatow and meet the pilot in the hangar basement to change into flying clothing, brief on any specific target and authorise the sortie. They would then go upstairs to the aircraft and go through the procedure I described earlier with the observer seated in the front cockpit carrying his camera, several rolls of film, a notebook and an extra lens which might be as much as 1000 mm - a big piece of kit! In the already cramped cockpit of the Chipmunk, changing film and lenses became a challenging task in itself.

An added complication was the fact that all this equipment could be considered more than a little suspicious in the event of a forced landing somewhere inside the DDR. The suggestion that we should get out, stow our equipment into a green bag and throw it all into a convenient lake was not taken seriously so the solution was to open the fuel drain cocks under the wings and set fire to the whole shooting match using the survival mini-flares we always carried. Fortunately the inherent reliability of the 145 HP Gipsy Major engine, allied to the dedication of our superb engineering staff, meant that no such eventuality ever occurred. Given that operational missions added up to about 250 hours flight time per year over a period of some 34 years, that's a total of 8,500 hours which, at the Chipmunk's cruising epeed of 90 knots, equates to well over ¾ million miles.

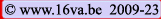

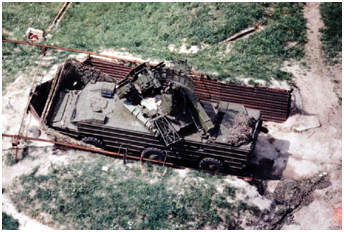

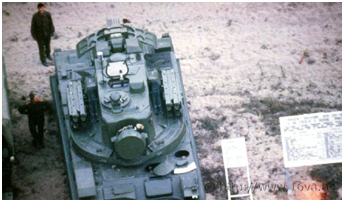

Back to our typical flight. Once airborne we set off on a roughly circular route starting with the local Potsdam area including a Guards Tank division at Krampnitz, a motor rifle division at Döberitz and an artillery division where they had the rather disturbing habit of training their guns on us and using us for tracking and sighting exercises. On one occasion we even captured a soldier pointing his Kalashnikov at us (> Link). We would then fly on to the rail sidings that served these units and their associated training areas. The reason for this concentrated effort was so we could report any activity to those officers who were going to be on a ground tour in the Potsdam area over the next 24 hours and so help them to avoid being caught up in any potential trouble.

So, let's look at a typical sortie. On the morning of a planned BRIXMIS flight a specialist officer or SNCO would drive down to Gatow and meet the pilot in the hangar basement to change into flying clothing, brief on any specific target and authorise the sortie. They would then go upstairs to the aircraft and go through the procedure I described earlier with the observer seated in the front cockpit carrying his camera, several rolls of film, a notebook and an extra lens which might be as much as 1000 mm - a big piece of kit! In the already cramped cockpit of the Chipmunk, changing film and lenses became a challenging task in itself.

An added complication was the fact that all this equipment could be considered more than a little suspicious in the event of a forced landing somewhere inside the DDR. The suggestion that we should get out, stow our equipment into a green bag and throw it all into a convenient lake was not taken seriously so the solution was to open the fuel drain cocks under the wings and set fire to the whole shooting match using the survival mini-flares we always carried. Fortunately the inherent reliability of the 145 HP Gipsy Major engine, allied to the dedication of our superb engineering staff, meant that no such eventuality ever occurred. Given that operational missions added up to about 250 hours flight time per year over a period of some 34 years, that's a total of 8,500 hours which, at the Chipmunk's cruising epeed of 90 knots, equates to well over ¾ million miles.

Back to our typical flight. Once airborne we set off on a roughly circular route starting with the local Potsdam area including a Guards Tank division at Krampnitz, a motor rifle division at Döberitz and an artillery division where they had the rather disturbing habit of training their guns on us and using us for tracking and sighting exercises. On one occasion we even captured a soldier pointing his Kalashnikov at us (> Link). We would then fly on to the rail sidings that served these units and their associated training areas. The reason for this concentrated effort was so we could report any activity to those officers who were going to be on a ground tour in the Potsdam area over the next 24 hours and so help them to avoid being caught up in any potential trouble.

Continuing our flight to the North of the BCZ we would observe and photograph the transport helicopter base at Oranienburg which was close to the notorious Sachsenhausen concentration camp which had been preserved by the Soviets, both as a fearsome reminder of the Nazi regime but also to house those that the communist authorities wanted to detain and punish. Since there was rarely any flying we were able to get close enough to get some very good shots. The reconnaissance base at Werneuchen, home to the Yak 28 "Brewer" and Mig 25 "Foxbat" aircraft was another target where there was also not a lot of aerial activity. Access to this airfield was almost impossible for a ground tour as it lay well inside the Permanent Restricted Area that even BRIXMIS personnel were forbidden to enter. The Foxbat was a formidable aircraft capable of speeds up to Mach 3 and heights of up to 70,000ft, predominately on reconnaissance missions but also with a secondary nuclear capability which would pose an even more serious threat in the event of a total conflict. On the odd occasion such as this we were able to catch aircraft out in the open being prepared for a reconnaissance mission but, at other times there was very little activity and ground crews would come out and wave at us. On the whole there was none of the hostility that their Army counterparts sometimes displayed. Indeed there were even reports of them enjoying an impromptu aerobatics display conducted by one of my predecessors.

To the South of Werneuchen there were some installations belonging to the East German Army and Border Guards including a barracks at Gossen where they had built a 400 metre exact replica of the Berlin Wall where new recruits could be trained.

Continuing our flight to the North of the BCZ we would observe and photograph the transport helicopter base at Oranienburg which was close to the notorious Sachsenhausen concentration camp which had been preserved by the Soviets, both as a fearsome reminder of the Nazi regime but also to house those that the communist authorities wanted to detain and punish. Since there was rarely any flying we were able to get close enough to get some very good shots. The reconnaissance base at Werneuchen, home to the Yak 28 "Brewer" and Mig 25 "Foxbat" aircraft was another target where there was also not a lot of aerial activity. Access to this airfield was almost impossible for a ground tour as it lay well inside the Permanent Restricted Area that even BRIXMIS personnel were forbidden to enter. The Foxbat was a formidable aircraft capable of speeds up to Mach 3 and heights of up to 70,000ft, predominately on reconnaissance missions but also with a secondary nuclear capability which would pose an even more serious threat in the event of a total conflict. On the odd occasion such as this we were able to catch aircraft out in the open being prepared for a reconnaissance mission but, at other times there was very little activity and ground crews would come out and wave at us. On the whole there was none of the hostility that their Army counterparts sometimes displayed. Indeed there were even reports of them enjoying an impromptu aerobatics display conducted by one of my predecessors.

To the South of Werneuchen there were some installations belonging to the East German Army and Border Guards including a barracks at Gossen where they had built a 400 metre exact replica of the Berlin Wall where new recruits could be trained.

Rather more importantly, a crew flying near Alt Rüdersdorf on the eastern edge of the BCZ came across a large excavation area at Kagel and took a number of photographs. They had accidentally discovered what was to become a target of high priority as the Soviets were in the process of installing a large aerial and burying it in the ground that would allow direct communication with Moscow. There had been intelligence concerning such a development but nobody had any idea of what to look for until the Chipmunk came across it. For the next 18 months it was regularly monitored and every stage of its construction was recorded which was just as well for within 2 years there was absolutely no sign that anything had ever happened there (1). The main problem with that was the fact that the site at Kagel actually lay outside the BCZ; had such a breach of the regulations been reported it could have led to serious repercussions.

All our flights were forensically examined after our images were processed. Not long after I arrived I was summoned to the BRIXMIS HQ which was housed, not in the Mission House in Potsdam but in the Berlin Olympic Stadium. On arrival I was kept waiting at the door while all the images that were displayed on the wall were covered up. Although I had been flying the aircraft, I was not allowed to see the results! When I finally got in I was told that some triangulation of a few of our images from the previous day had proved that I had ventured some 200 yards outside the BCZ and I was warned that any subsequent offence could lead to my summary return to the UK. The fact that I had been directed there by my more experienced observer was no defence. I was the captain of the aircraft so it was down to me to know exactly where I was at all times.

Many of the images obtained by the operation were incredibly clear and often captured details of new equipment never previously seen outside the Soviet Union. To this day there is not much of it available in the public domain and, to be fair, is only of historic interest anyway. But it is worth bearing in mind that it was all obtained by means of an observer operating a hand-held camera in the front seat of the Chipmunk being flown by a pilot in the rear cockpit. To achieve the clearest results, the canopy had to be partially opened and the camera held clear of the aircraft structure to avoid vibration. In the depths of the Berlin winter when temperatures could be as low as minus 20 decrees Celsius, added to the wind chill factor of the 90kt airflow, this was extremely challenging. I was very glad that my short participation was exclusively conducted in mid-Summer!

Rather more importantly, a crew flying near Alt Rüdersdorf on the eastern edge of the BCZ came across a large excavation area at Kagel and took a number of photographs. They had accidentally discovered what was to become a target of high priority as the Soviets were in the process of installing a large aerial and burying it in the ground that would allow direct communication with Moscow. There had been intelligence concerning such a development but nobody had any idea of what to look for until the Chipmunk came across it. For the next 18 months it was regularly monitored and every stage of its construction was recorded which was just as well for within 2 years there was absolutely no sign that anything had ever happened there (1). The main problem with that was the fact that the site at Kagel actually lay outside the BCZ; had such a breach of the regulations been reported it could have led to serious repercussions.

All our flights were forensically examined after our images were processed. Not long after I arrived I was summoned to the BRIXMIS HQ which was housed, not in the Mission House in Potsdam but in the Berlin Olympic Stadium. On arrival I was kept waiting at the door while all the images that were displayed on the wall were covered up. Although I had been flying the aircraft, I was not allowed to see the results! When I finally got in I was told that some triangulation of a few of our images from the previous day had proved that I had ventured some 200 yards outside the BCZ and I was warned that any subsequent offence could lead to my summary return to the UK. The fact that I had been directed there by my more experienced observer was no defence. I was the captain of the aircraft so it was down to me to know exactly where I was at all times.

Many of the images obtained by the operation were incredibly clear and often captured details of new equipment never previously seen outside the Soviet Union. To this day there is not much of it available in the public domain and, to be fair, is only of historic interest anyway. But it is worth bearing in mind that it was all obtained by means of an observer operating a hand-held camera in the front seat of the Chipmunk being flown by a pilot in the rear cockpit. To achieve the clearest results, the canopy had to be partially opened and the camera held clear of the aircraft structure to avoid vibration. In the depths of the Berlin winter when temperatures could be as low as minus 20 decrees Celsius, added to the wind chill factor of the 90kt airflow, this was extremely challenging. I was very glad that my short participation was exclusively conducted in mid-Summer!

Conclusion

Following German reunification there was obviously no longer any need for the various military missions and BRIXMIS was formally disbanded on 31 December 1990. As I mentioned earlier, 31 members could be "on pass" at any time but the total strength of the unit was much higher. There were a total of 68 personnel, including 25 RAF personnel at the end. There was actually one fish-head in 1988 but no-one was quite sure why he was there!

So, what was it all about and was all the secrecy really warranted. There is no doubt that some of the intelligence gathered and the images obtained were extremely valuable and maybe more detailed than the Soviets imagined. But the BRIXMIS flights, together with parallel missions flown by the Americans and the French were hardly clandestine. A small aircraft pottering around at lower than 1,000 ft with a camera lens poking out of one side was fairly obvious, indeed on one famous occasion an American photographer while changing lenses managed to drop one out of the aircraft on to a busy parade ground at a Soviet barracks (See "Operation Larkspur" > Link). At any time one of these aircraft could have been shot or forced down but there was always the slight risk that the particular flight was quite innocent. The Gatow QFI flew around the area on an almost daily basis often without a BRIXMIS observer on board, sometimes

carrying a very senior RAF or Army officer on a sort of sightseeing trip and the political repercussions of getting the wrong aircraft can only be imagined. There was also a theory that many in the Soviet high command were quite happy to let the Allies see their capability as a sort of deterrent policy. After all, many of them had graphic memories of the Great Patriotic War and had no wish to see it repeated. With hindsight I can see why the detailed results of the operation were highly classified but the secrecy with which it was conducted does seem now to be faintly ridiculous. One of my lasting memories is of a cocktail party at which a Soviet captain came up to me and asked if it was true that I was the Chipmunk pilot. When I said "Yes", he said: "I have many photographs of you taking photographs of me." They did have a sense of humour!

Following German reunification there was obviously no longer any need for the various military missions and BRIXMIS was formally disbanded on 31 December 1990. As I mentioned earlier, 31 members could be "on pass" at any time but the total strength of the unit was much higher. There were a total of 68 personnel, including 25 RAF personnel at the end. There was actually one fish-head in 1988 but no-one was quite sure why he was there!

So, what was it all about and was all the secrecy really warranted. There is no doubt that some of the intelligence gathered and the images obtained were extremely valuable and maybe more detailed than the Soviets imagined. But the BRIXMIS flights, together with parallel missions flown by the Americans and the French were hardly clandestine. A small aircraft pottering around at lower than 1,000 ft with a camera lens poking out of one side was fairly obvious, indeed on one famous occasion an American photographer while changing lenses managed to drop one out of the aircraft on to a busy parade ground at a Soviet barracks (See "Operation Larkspur" > Link). At any time one of these aircraft could have been shot or forced down but there was always the slight risk that the particular flight was quite innocent. The Gatow QFI flew around the area on an almost daily basis often without a BRIXMIS observer on board, sometimes

carrying a very senior RAF or Army officer on a sort of sightseeing trip and the political repercussions of getting the wrong aircraft can only be imagined. There was also a theory that many in the Soviet high command were quite happy to let the Allies see their capability as a sort of deterrent policy. After all, many of them had graphic memories of the Great Patriotic War and had no wish to see it repeated. With hindsight I can see why the detailed results of the operation were highly classified but the secrecy with which it was conducted does seem now to be faintly ridiculous. One of my lasting memories is of a cocktail party at which a Soviet captain came up to me and asked if it was true that I was the Chipmunk pilot. When I said "Yes", he said: "I have many photographs of you taking photographs of me." They did have a sense of humour!

This has all been about RAF Gatow but, inevitably a lot has been about me so I'd like to end this article with a couple of personal reminiscences. One of the favours that Werner Muths did me was to introduce me to a wonderful group of former Luftwaffe aircrew from World War 2 known as the Jägerkreis. On 11 October 1991 the national organisation held its annual reunion in Berlin, the first time this had been possible. We held a reception for them at Gatow and, amongst others I got to meet the famous Adolf Galland.

I also got to meet Günther Rall, the 3rd highest scoring Luftwaffe fighter ace with 275 victories all but 3 of them on the Eastern Front. He was shot down 8 times and wounded 3 times, on one occasion being hospitalised for nearly 12 months having been paralysed down his right side. Unlike their RAF counterparts, the Luftwaffe pilots didn't have specific tours of duty - if they were fit they flew. Rall's recollection: "It seemed to me at the time that I was either in a hospital bed or a 109 cockpit". In one incident he had his left thumb shot off and when I commented that he still returned to combat, his laconic reply was: "It was OK, I only needed my right thumb for the firing button."

One of my last flights took place on 20th October 1993 when the oldest Junkers 52 still flying, visited Berlin and I was able to persuade the pilot to fly over Gatow and allow me to join him in a formation flypast. The iconic Ju 52 first flew in 1932 and by sheer coincidence this one first got airborne in 1936, the year that Luftkriegschule 2 was opened in Gatow. I have never conformed to the convention of referring to an aircraft as "she", to me they are always "it". But this one has to be an exception as she is known universally by the soubriquet "Tante Ju". She is now owned and operated by Deutsche Lufthansa Berlin-Stiftung based in Hamburg. She flew until 2019 all over Germany offering sightseeing trips lasting 30 mins for a remarkable 239 Euros [the Ju 52 is now grounded and preserved]. By comparison, if you visit the East Kirkby Air Museum in Lincolnshire, you can enjoy a short taxy ride in their Lancaster for just £325!

And finally, where are the Chipmunks now? There were many down the years but of the two I flew WG466 is back at Gatow as an exhibit in the Luftwaffe museum [renamed to Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr] based there while the one I regard as mine, WG486, has been repainted in a shiny black livery and is used by the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight to introduce new pilots to the delights, mysteries and challenges of the noble art of what is known as "taildragging".

This has all been about RAF Gatow but, inevitably a lot has been about me so I'd like to end this article with a couple of personal reminiscences. One of the favours that Werner Muths did me was to introduce me to a wonderful group of former Luftwaffe aircrew from World War 2 known as the Jägerkreis. On 11 October 1991 the national organisation held its annual reunion in Berlin, the first time this had been possible. We held a reception for them at Gatow and, amongst others I got to meet the famous Adolf Galland.

I also got to meet Günther Rall, the 3rd highest scoring Luftwaffe fighter ace with 275 victories all but 3 of them on the Eastern Front. He was shot down 8 times and wounded 3 times, on one occasion being hospitalised for nearly 12 months having been paralysed down his right side. Unlike their RAF counterparts, the Luftwaffe pilots didn't have specific tours of duty - if they were fit they flew. Rall's recollection: "It seemed to me at the time that I was either in a hospital bed or a 109 cockpit". In one incident he had his left thumb shot off and when I commented that he still returned to combat, his laconic reply was: "It was OK, I only needed my right thumb for the firing button."

One of my last flights took place on 20th October 1993 when the oldest Junkers 52 still flying, visited Berlin and I was able to persuade the pilot to fly over Gatow and allow me to join him in a formation flypast. The iconic Ju 52 first flew in 1932 and by sheer coincidence this one first got airborne in 1936, the year that Luftkriegschule 2 was opened in Gatow. I have never conformed to the convention of referring to an aircraft as "she", to me they are always "it". But this one has to be an exception as she is known universally by the soubriquet "Tante Ju". She is now owned and operated by Deutsche Lufthansa Berlin-Stiftung based in Hamburg. She flew until 2019 all over Germany offering sightseeing trips lasting 30 mins for a remarkable 239 Euros [the Ju 52 is now grounded and preserved]. By comparison, if you visit the East Kirkby Air Museum in Lincolnshire, you can enjoy a short taxy ride in their Lancaster for just £325!

And finally, where are the Chipmunks now? There were many down the years but of the two I flew WG466 is back at Gatow as an exhibit in the Luftwaffe museum [renamed to Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr] based there while the one I regard as mine, WG486, has been repainted in a shiny black livery and is used by the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight to introduce new pilots to the delights, mysteries and challenges of the noble art of what is known as "taildragging".

© Tony Bowen

Notes

(1) It was most likely the East German Ministry of National Defense radio transmission center in Kagel, which included a buried antenna > Link. The transmitter "M" operated a buried loop antenna and transmitted an identification code several times per minute, the change of which was intended to signal alarm conditions or an emergency.

| RAF Gatow Station Flight Chipmunks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Serial | In | Out |

| WD289 | 10.04.75 | 01.06.87 |

| WG303 | 10.12.56 | 29.04.68 |

| WG466 | 08.05.87 | 1994 |

| WG478 | 05.87 | 1994? |

| WG486 | 08.05.87 | 1994 |

| WK587 | 09.11.62 | 29.04.68 |

| WP850 | 30.04.68 | 17.11.75 |

| WP971 | 30.04.68 | 28.10.75 |

| WZ862 | 05.12.74 | 01.06.87 |

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |