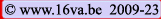

La console du CWAR à gauche et la console principale du BCC, à droite. © L.Schmitz.

La console du CWAR à gauche et la console principale du BCC, à droite. © L.Schmitz.

From left to right, the CWAR console and the main display of the BCC. © L.Schmitz.

As soon as the night fell, the battery moved towards Mengeringhausen, an exercise ground nearby. It was late and as they had

drunk too much the night before, the evaluators asked their driver to take them back to the hotel. Once they were gone, a

rotation of vehicles was organized to bring back our personnel to their quarters. Some volunteers would remain on site to act

as if everyone was present. The battery commander was taking a big risk, but he knew that with a good night's sleep, his men

would work much better the next day. During wartime, everything is allowed, right? Alone in the BCC, I simulated attacks of

enemy aircraft all night long - in fact, innocent airliners...

The next morning, was catastrophic. The evaluators overtook the column of trucks bringing our men back to the site. Fortunately,

the driver of the minibus had the presence of mind to ‘get lost’ in the thick fog that covered the area that morning. When the

evaluators arrived at the site the men were back at their posts, fresh as a daisy. I needed to sleep for a few hours. I had

bought a ‘Bivibag’ from the British Army, a Gore-Tex shelter making it possible to sleep anywhere. In order to protect me from

the rain, while remaining nearby, I lay down under the truck carrying the BCC. The place was horribly noisy, so I slept with my

hearing protections. A disturbing silence suddenly woke me up. Above me, the truck was gone. It was moved during my sleep and

with the fog, no one saw me. Fortunately, I had not been crushed and the battery was not very far. I could hear the hum of a

generator somewhere on my right.

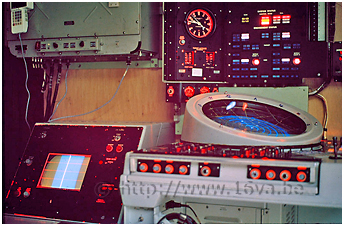

Le BCC était plutôt exigu. © L.Schmitz.

Le BCC était plutôt exigu. © L.Schmitz.

The BCC was rather cramped. © L.Schmitz.

At night, the amazed evaluators watched the arrival of a taxi being towed by one of our missile loading vehicles in order not to

get stuck in the mud.

The German driver was transporting 87 hot pizzas and a can of beer per person, while the evaluators had to content with their

combat rations and a can of coke. I turned towards an American officer: “Would you like a slice of pizza? Help yourself,

there’s plenty left”. The major sat next to me to enjoy his ‘Cappricciosa’ and a Jupiler beer. “You guys are unbelievable!”.

Inside the BCC my BCA was copying a secret list with incidents, which the Yank had left on his chair. It was war, wasn’t it?

A chemical attack surprised us at dawn. Wearing a gas mask even with a cartridge filter emptied of its content is not comfortable.

Just try to speak on the radio with that thing over your face! Moreover, the BCC was crowded. The 3 by 2 meters large container

hosted 7 people and their working stations: the BCO, the BCA, the two HPIR operators, the CWAR operator, a soldier who made the

liaison with the PC and moreover, the American evaluator. Well, at least nobody was smoking… Bad luck: the PAR went suddenly

unserviceable and we had to move it away. We received another one, but while we were assembling it, we found out that we had

received two left reflectors… Followed a great palaver with the chief repairman. The American was already noting on a form that

the battery was not operational. In times of hardship, you have to make do with what you have! I decided to run the radar with

only a half antenna. The predictions went full swing: some thought that the radar would turn over immediately; others thought

that it would twist. The majority thought that the vibrations would prevent a normal detection. The radar took finally its

twenty turns per minute without problems in front of a speechless evaluator.

An echo at 85 km indicated that it was working rather well and the combat resumed again. The vexed American corrected his form

and shook his head: “you guys are incredible!”…

Shortly after, the war was over. Once again, the Alpha battery had saved the free world. It was rewarded with an ‘Excellent’,

and the battalion received a global ‘Satisfactory’ score.

Playing cat and mouse

Chaque batterie possédait quelques affûts AA triples. Ces antiques canons Hispano de 20mm à chargeurs "tambour"

étaient destinés à la défense rapprochée des sites. Lors des "taceval" la batterie Alpha simulait des canons supplémentaires à

l'aide de tubes destinés normalement à lever les filets de camouflage. Un leurre aussi bon marché qu'efficace!

© Collection M.Wyffels.

Chaque batterie possédait quelques affûts AA triples. Ces antiques canons Hispano de 20mm à chargeurs "tambour"

étaient destinés à la défense rapprochée des sites. Lors des "taceval" la batterie Alpha simulait des canons supplémentaires à

l'aide de tubes destinés normalement à lever les filets de camouflage. Un leurre aussi bon marché qu'efficace!

© Collection M.Wyffels.

Each Hawk battery was equipped with old Hispano 20mm guns for close protection. © M.Wyffels collection.

Spring is not only the season for little birds, but also for airmen of all kinds. After months of reduced activity due to the weather,

they must make up for the lost time and build up hours. Each day the F-16, F-18 and Mirage were simulating attacks on the site.

This morning for example, Lynx helicopters from Paderborn were attacking us. Of course, we shot down all of them. Too easy: the

HPIR detected the rotation of their rotor dsics without any problem. You could shot them even before they took off! Sometimes,

the Russians woke up. Between Kassel and Leipzig, the border formed a corner planted in West Germany. Sometimes the MiG-25

patrol launched at Mach 2 along the Iron Curtain cut the corner for a few seconds. Perestroika or not, the Soviet Army

remained a formidable opponent and it intended to remind it to us from time to time.

Periodically, the NATO CRC (Command and Reporting Center) sent us a ‘Zombie Warning’. A ‘Zombie’ was a civilian aircraft

suspected of being equipped with electronic spying equipment. We then avoided activating the radar in order not to reveal our

frequencies, even if the rumor went that the Soviets knew the Hawk better than us! A colleague told me that in 1987, the radar

site at Oesdorf (Charlie battery) was jammed by a strange noise coming from a point nearby in West Germany. After several hours,

the firing officer drove with a jeep to the suspected coordinates. To his surprise, the place was a parking place along the

Autobahn Dortmund-Kassel. A large semi-trailer equipped with ‘TIR’ plates had been parked there for several days,

which had also aroused the suspicions of the maintenance crews. The electronic jamming ceased on the arrival of the

Polizei and security officers. The truck was then escorted back to East Germany

(1).

‘Reds’ were not the only one to try to jam us. US EF-111 ECM aircraft sometimes sent ‘Music’ to our antennas but with only a

limited success. The ECCM equipments of the Hawk were very efficient. The fighter aircraft threw aluminum strips (chaff) that

had absolutely no effect. However, one aircraft seemed really capable of making us blind: the B-52. I have never witnessed it

myself, but colleagues assured me that its effects were spectacular. It was always possible to fire in the ‘Home on Jam’ mode,

but other targets were then hidden.

One summer evening, while the operators were training on airliners, an echo appeared at the north edge of the screen, away from

traditional airways. Already at the second revolution of the radar it was clear that this was not a normal customer. Both spots

were very distant from each other and the firing computer designated the object as ‘Cat One’... This aircraft was now the

greatest threat to the battery even if it was more than a hundred kilometers away. The first High-Power locked at a distance of

80 kilometers: "Alpha Skin Lock; Velocity Very High; Flight Level ... gosh!". On my indicator, the needle was stuck at the top of

the graduations. The target had to be at 30.000 meters. It flew incredibly fast and the radar was locked on its fuselage instead

of the blades of the reactor fans. The ‘PIP’ (Predicted Intercept Point) already exceeded the battery: it was now almost

impossible to fire. We observed the unusual aircraft crossing the screen from north to south in a few antenna revolutions.

Its speed was much higher than that of an anti-radiation missile and the echo on the ‘Velocity Scope’ of the High Power floated

to the far right near 4.000km/h! At that time, the SR-71 spy plane was the only aircraft capable of such a performance. We

watched the sky in vain as no vapor trail betrayed the passage of the mysterious aircraft in the stratosphere...

(see > Intercepting the blackbird).

‘Reds’ were not the only one to try to jam us. US EF-111 ECM aircraft sometimes sent ‘Music’ to our antennas but with only a

limited success. The ECCM equipments of the Hawk were very efficient. The fighter aircraft threw aluminum strips (chaff) that

had absolutely no effect. However, one aircraft seemed really capable of making us blind: the B-52. I have never witnessed it

myself, but colleagues assured me that its effects were spectacular. It was always possible to fire in the ‘Home on Jam’ mode,

but other targets were then hidden.

One summer evening, while the operators were training on airliners, an echo appeared at the north edge of the screen, away from

traditional airways. Already at the second revolution of the radar it was clear that this was not a normal customer. Both spots

were very distant from each other and the firing computer designated the object as ‘Cat One’... This aircraft was now the

greatest threat to the battery even if it was more than a hundred kilometers away. The first High-Power locked at a distance of

80 kilometers: "Alpha Skin Lock; Velocity Very High; Flight Level ... gosh!". On my indicator, the needle was stuck at the top of

the graduations. The target had to be at 30.000 meters. It flew incredibly fast and the radar was locked on its fuselage instead

of the blades of the reactor fans. The ‘PIP’ (Predicted Intercept Point) already exceeded the battery: it was now almost

impossible to fire. We observed the unusual aircraft crossing the screen from north to south in a few antenna revolutions.

Its speed was much higher than that of an anti-radiation missile and the echo on the ‘Velocity Scope’ of the High Power floated

to the far right near 4.000km/h! At that time, the SR-71 spy plane was the only aircraft capable of such a performance. We

watched the sky in vain as no vapor trail betrayed the passage of the mysterious aircraft in the stratosphere...

(see > Intercepting the blackbird).

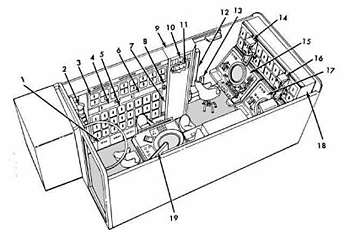

La zone couverte par les deux bataillons belges (43A en mauve et 62A en turquoise) était considérable. Il s'agit

ici d'une situation temps de paix avec seulement deux sites actifs. En temps de guerre, trois sites (quatre avant 1979)

étaient actifs par bataillon,

mais comme ils étaient situés dans une même zone, la superficie couverte n'était guère plus grande que celle représentée ici.

La zone couverte par les deux bataillons belges (43A en mauve et 62A en turquoise) était considérable. Il s'agit

ici d'une situation temps de paix avec seulement deux sites actifs. En temps de guerre, trois sites (quatre avant 1979)

étaient actifs par bataillon,

mais comme ils étaient situés dans une même zone, la superficie couverte n'était guère plus grande que celle représentée ici.

The area covered by the two Belgian Hawk battalions (43A in purple and 62A in turquoise) was considerable. This is a peacetime

situation with only two sites actives. In case of war, three sites (four before 1979) would have been active for each

battalion. As they were located in a same area, the area covered would have been nearly the same as shown here.

Since the Battle of Britain, the airmen think that flying low is enough to avoid being detected. Unfortunately for them, this

is only true for primitive radars, whose beam must be pointed to the sky in order to avoid the echoes from ‘Ground Clutter’.

For modern radars, anything that moves is picked up, regardless of its altitude. Worse still, the firing computer always assigns

a higher threat level to a plane flying close to the ground. Unless you hide behind an impenetrable object (hill, mountain

terrain) flying at low level only makes you suspicious. You are also very vulnerable to short-range weapons.

Another myth is that if two planes constantly cross their path while approaching a radar, they can not be shot down. This tactic

called ‘Cobra’ and often used by the A-10 was absolutely futile. To enter ‘Zero Doppler’ conditions, an aircraft must have a zero approach

speed relative to the radar. This only happens when the aircraft remains at a constant distance from the radar. In that case,

it is actually impossible to get a ‘Lock’. But this is not necessary as the attacker is not a threat at all as it is not

approaching. Moreover, when it is in ‘Zero Doppler’ for a radar it is most likely in a favorable position for the other

batteries. A SAM defense always included at least three batteries. And even if only one tracking radar was available, the

‘Cobra’ could only fool a newbie operator. Any expert would switch to manual mode and continue to follow the target despite its evading maneuvers. In automatic mode,

the radar switched from one aircraft to the other.

The missile would have been forced to slalom, but would have approached

close enough anyway. Better yet, the two attackers would have been victims of the same missile, as they flew too close to each

other. To my knowledge, the only efficient tactic was successfully used once by Canadians F/A-18.

To avoid the detection of cars on the German motorways, the radars were usually set to ignore anything that moved at less than

160km/h. Two Canadian pilots were able to approach our battery ‘incognito’, flying with landing gear and flaps down at low

speed. When they reached Arolsen area, they banked towards the battery and simulated the firing of two HARM missiles: not

seen, not caught! This maneuver was intelligent, but unrealistic because in time of war an F-18 flying with its nose up at

low speed would have been an excellent target for ground troops. The young Mathias Rust used the same trick to land his

Cessna 152 on the Red Square, after 800 km of slow flying through Soviet defenses.

The missile would have been forced to slalom, but would have approached

close enough anyway. Better yet, the two attackers would have been victims of the same missile, as they flew too close to each

other. To my knowledge, the only efficient tactic was successfully used once by Canadians F/A-18.

To avoid the detection of cars on the German motorways, the radars were usually set to ignore anything that moved at less than

160km/h. Two Canadian pilots were able to approach our battery ‘incognito’, flying with landing gear and flaps down at low

speed. When they reached Arolsen area, they banked towards the battery and simulated the firing of two HARM missiles: not

seen, not caught! This maneuver was intelligent, but unrealistic because in time of war an F-18 flying with its nose up at

low speed would have been an excellent target for ground troops. The young Mathias Rust used the same trick to land his

Cessna 152 on the Red Square, after 800 km of slow flying through Soviet defenses.

notes

(1) The East German international road transport company Deutrans was known to serve as a cover for espionage activities in the West > Link. One of their vehicles was likely involved in the incident mentioned here. It is quite possible that the semitrailer was carrying the same "Smal'ta" ECM system as the Mi-8SMV (see > The Mi-8, Part 4). That electronic suite was indeed designed to jam the Hawk missiles. The complex had very small squared antennas (about the size of a Mi-8 cabin window) that could easily have been mounted behind dielectric panels located on the sides of the trailer. HM.

|

The Hawk batteries < Part 1 < Part 2 < Part 3 < Part 4 |

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |