Radim Špalek wrote a four part article entitled "Rocket Launched!" about the live missile firing campaigns of the Czechoslovak and later Czech fighters in the USSR, the GDR, Poland and Sweden between 1959 and 2023. He detailes for us the East German period.

The Baltic Zone in the GDR 1972-1990

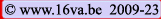

Une cible M-6 dans le viseur ! © Collection R.Špalek.

Une cible M-6 dans le viseur ! © Collection R.Špalek.

An M-6 target in the crosshairs! © R.Špalek Collection

The term "Baltic Zone" referred to an area of approximately 20 x 50 km north of the island of Usedom, known for Nazi rocket research that was conducted there during World War II. It was one of the GDR's firing ranges, administered by the 16.VA. Live-fire exercises were organized here by the Soviets, East Germans and Hungarians (1). An important aspect was the possibility of reaching the zone directly from Czechoslovakia with a MiG-21, eliminating the need for support equipment. These flights, of course, required significant concentration and coordination from the pilots and security personnel. The necessary formalities were completed in 1971, and the first firing camp began in the spring of 1972.

Colonel (retired) Josef Pavlík, then inspector of attack aircraft and air gunnery at the 7th Army PVOS (State Air Defence), who played a key role in organizing live-fire air-to-air missile training in the GDR, recalls what these "formalities" entailed:

"We knew that firing ranges existed on the Baltic Sea coast, used not only by the Soviet Air Force, but also by the East German Air Force or the Hungarian Air Force (sic). Despite the secrecy surrounding these ranges, in 1970 our command sent letters to the general staffs of the German People's Army and the Polish People's Army to inquire whether the Czechoslovak People's Army Air Force could use these ranges. The reply came quickly, and we then learned that these firing ranges were indeed located in the Baltic Sea and that there were others. The first was located west of the island of Rügen, but was intended solely for ground anti-aircraft fire. The second, east of Rügen, was used for air-to-air firing, and the third zone was off the Polish Baltic coast in the east (2). At the same time, we were informed that all these firing ranges were under the administration of the Soviet VVS in East Germany [not the Polish range]. Another letter, this time addressed to the General Staff of the Soviet Army in Moscow, met with surprising success - perhaps the consequences of the August 1968 occupation had some impact, positive or negative.

We received a "code" authorizing us to fire in zone No.2. Navigation calculations demonstrated that the MiG-21's range allowed it to reach the Baltic Sea coast and return to our air bases, primarily Žatec, without refueling. After gaining experience, the take-off and landing sites of the MiG-21 aircraft were expanded, so that eventually they were also flying from Líně airbase.

In 1971, a delegation led by Colonel Jan Jančík, then head of the Combat Training Department of the Air Force and Air Defense Command (VLaPVOS), Lt. Col. Ing. Hynek Hofman, Inspector of Fighter Aviation and myself, as Inspector of Air Gunnery, was flown to Sperenberg. We were received at the headquarters of the 16.VA in Wünsdorf by its commander, Colonel General A. N. Katrich (3) and other officers. The main organizational details of the event were finalized there. On the same day, this delegation accompanied by the head of Gunnery and Tactical Training of the 16.VA, flew to Damgarten where the 82nd Aviation Polygon, which managed the firing range, was located. Here, we were given the "Directives for the implementation of combat firing training on M-6 bomb-targets and RM-3V missiles (Raketa-Mishen' - missile-target) in the area of air-to-air firing range No.2 [Luftschießzone II]". We agreed on the precise firing dates, air traffic control procedures and the flight route.

Interestingly, we did not obtain the radio navigation data and other information on the air bases necessary for overflying the East German territory, as one might have expected, in Wünsdorf (where we had been advised to request them "via Moscow"), but directly from the firing range command post (VS) at Damgarten. A few toasts with imported Becherovka beer were all it took. This is how we received the necessary data for practically the entire firing organization period, even though some officials tried to get it through a truly official channel via Moscow."

Žatec was chosen as the most suitable departure base due to its geographical location. A little later, however, flights over the "Zóna Balt" also departed from Plzeň-Líně and occasionally from Bechyně or České Budějovice. Subsequently, Žatec served as a forward operating base mostly for the fighter regiments of the 7th Army PVOS (A PVOS), and Líně for units of the 10th Air Army (LA).

As for the aircrew, training was perfectly streamlined. Not only 1st class pilots but also junior lieutenants sat in the cockpits of the "twenty-ones", and members of the fighter divisions and the general staff also participated.

In 1971, a delegation led by Colonel Jan Jančík, then head of the Combat Training Department of the Air Force and Air Defense Command (VLaPVOS), Lt. Col. Ing. Hynek Hofman, Inspector of Fighter Aviation and myself, as Inspector of Air Gunnery, was flown to Sperenberg. We were received at the headquarters of the 16.VA in Wünsdorf by its commander, Colonel General A. N. Katrich (3) and other officers. The main organizational details of the event were finalized there. On the same day, this delegation accompanied by the head of Gunnery and Tactical Training of the 16.VA, flew to Damgarten where the 82nd Aviation Polygon, which managed the firing range, was located. Here, we were given the "Directives for the implementation of combat firing training on M-6 bomb-targets and RM-3V missiles (Raketa-Mishen' - missile-target) in the area of air-to-air firing range No.2 [Luftschießzone II]". We agreed on the precise firing dates, air traffic control procedures and the flight route.

Interestingly, we did not obtain the radio navigation data and other information on the air bases necessary for overflying the East German territory, as one might have expected, in Wünsdorf (where we had been advised to request them "via Moscow"), but directly from the firing range command post (VS) at Damgarten. A few toasts with imported Becherovka beer were all it took. This is how we received the necessary data for practically the entire firing organization period, even though some officials tried to get it through a truly official channel via Moscow."

Žatec was chosen as the most suitable departure base due to its geographical location. A little later, however, flights over the "Zóna Balt" also departed from Plzeň-Líně and occasionally from Bechyně or České Budějovice. Subsequently, Žatec served as a forward operating base mostly for the fighter regiments of the 7th Army PVOS (A PVOS), and Líně for units of the 10th Air Army (LA).

As for the aircrew, training was perfectly streamlined. Not only 1st class pilots but also junior lieutenants sat in the cockpits of the "twenty-ones", and members of the fighter divisions and the general staff also participated.

After 1984, several pilots of the 6th sbolp (fighter-bomber aviation regiment) from Přerov, the 47th pzlp (reconnaissance aviation regiment) from Hradec Králové and the 1st lšp (aviation school regiment) from Přerov also flew over the "Zóna Balt". Until then, this training was carried out only by pilots from the 1st, 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th and 11th slp (fighter aviation regiments).

The flights took place from spring to autumn, and especially in summer, when weather conditions were most favorable. For example, as early as the first year in 1972, the 7th A PVOS and the 10th LA conducted firing exercises every five days during the first half of June. They took off regardless of weather conditions, practically at any time of day or night. Flights in adverse weather conditions (ZPP) and in adverse conditiona at nigt (ZPPN)

were no exception, when most of the route was flown in clouds in IFR conditions. The only requirement for executing the planned firing exercises was good visibility in the target area, which meant a mostly clear sky. Flying over eastern Germany was no piece of cake in terms of radio communications, as the VVS lacked centralized air traffic control there. Several Soviet airbases took turns controlling aircraft across the GDR. Thus, to reach the firing range, our fighters used the liaison with the home command post as far as the Berlin area, from where they already reported to the firing range commander in Damgarten. When the radio communications were weak, a MiG-21U would sometimes fly over northern Bohemia at an altitude of 10,000 m, acting as a relay that transmitted reports from pilots heading towards the Baltic to our VS. Obtaining Soviet weather forecasts, crucial for these operations, was often difficult. In this particular case, our An-24V transport aircraft provided assistance. Flying over East Germany at an altitude of 6,500 meters, it mapped the situation along the route.

Zone No.2 extended into international waters of the Baltic Sea, which meant that it could not be declared dangerous to shipping. The guidelines for the operation of this firing range stipulated that the crews of Soviet An-26 relay and surveillance aircraft as well as those of the Il-28 target-carrying aircraft, had to report the presence of any ship in the area, which would result in the interruption of the firing exercice.

After 1984, several pilots of the 6th sbolp (fighter-bomber aviation regiment) from Přerov, the 47th pzlp (reconnaissance aviation regiment) from Hradec Králové and the 1st lšp (aviation school regiment) from Přerov also flew over the "Zóna Balt". Until then, this training was carried out only by pilots from the 1st, 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th and 11th slp (fighter aviation regiments).

The flights took place from spring to autumn, and especially in summer, when weather conditions were most favorable. For example, as early as the first year in 1972, the 7th A PVOS and the 10th LA conducted firing exercises every five days during the first half of June. They took off regardless of weather conditions, practically at any time of day or night. Flights in adverse weather conditions (ZPP) and in adverse conditiona at nigt (ZPPN)

were no exception, when most of the route was flown in clouds in IFR conditions. The only requirement for executing the planned firing exercises was good visibility in the target area, which meant a mostly clear sky. Flying over eastern Germany was no piece of cake in terms of radio communications, as the VVS lacked centralized air traffic control there. Several Soviet airbases took turns controlling aircraft across the GDR. Thus, to reach the firing range, our fighters used the liaison with the home command post as far as the Berlin area, from where they already reported to the firing range commander in Damgarten. When the radio communications were weak, a MiG-21U would sometimes fly over northern Bohemia at an altitude of 10,000 m, acting as a relay that transmitted reports from pilots heading towards the Baltic to our VS. Obtaining Soviet weather forecasts, crucial for these operations, was often difficult. In this particular case, our An-24V transport aircraft provided assistance. Flying over East Germany at an altitude of 6,500 meters, it mapped the situation along the route.

Zone No.2 extended into international waters of the Baltic Sea, which meant that it could not be declared dangerous to shipping. The guidelines for the operation of this firing range stipulated that the crews of Soviet An-26 relay and surveillance aircraft as well as those of the Il-28 target-carrying aircraft, had to report the presence of any ship in the area, which would result in the interruption of the firing exercice.

Col. Josef Pavlík again comes with a few observations:

"How could the crews detect the presence of a ship in total cloud cover without visibility of the sea or at night was not written anywhere. None of the responsible officials of the firing range dealt with this problem, at least during the firing of our pilots. Nevertheless, the shooting was interrupted several times, which the Soviet side justified by the arrival of strategic aircraft from the Leningrad area, and by the alleged activity of the Swedish Air Force over the Baltic. During the first shootings in the early 1970s, we suspected our "comrades-in-arms" of the 16.IAD of maintaining air readiness to prevent our pilots from flying to Sweden. This would have been quite easy to detect on the radar screen used to control our pilots' firings. They simply didn't trust us, as usual.

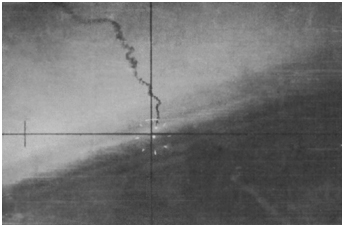

Zone No.2 was 50 kilometers long, 8 kilometers wide in the south, and 45 kilometers wide in the north. The approach was on a 360° course via Ahlbeck Airport [Garz, today Heringsdorf], and the departure after the firing was a left turn to a 210° course. Combat firing of the missiles was possible in the 340-010° sector at altitudes of up to 20,000 m during subsonic or supersonic flight, day and night, in normal and difficult weather conditions. The minimum flight altitude above the clouds was to be 2,000 m, but this was not strictly adhered to. Firing was possible at the level of Peenemünde airfield and ended at the level of the town of Binz on Rügen. Fire control, including radio and radar support, was carried out from the airport in Damgarten. Incidentally, this also served as the main backup base. We flew to Damgarten as firing controllers the day before the firing began in a group of 3-4 officers with a complete live combat firing planning table. To secure the firing, it was also necessary to bring our own targets to Damgarten, which were then dropped by Soviet Il-28s. For example, in 1976, the 1st Airborne Transport Regiment from Mošnov transported a total of 10 M-6 bombs and 20 SAB-100/90 illumination bombs to the GDR by air."

Due to the demanding nature of such flights, it was necessary to first thoroughly prepare the selected fighter pilots in a "domestic" environment. This preparation was incorporated into the training schedule for each unit and consisted of ground and flight components. The pilots refreshed their knowledge of Russian radio communication, tactical and technical data on the RS-2US (radar-guided), R-3S and later R-13M (infrared-guided) missiles, emergency procedures in the event of engine failure, radio stations, radio compasses, etc. during 30 hours classes of theory.

Col. Josef Pavlík again comes with a few observations:

"How could the crews detect the presence of a ship in total cloud cover without visibility of the sea or at night was not written anywhere. None of the responsible officials of the firing range dealt with this problem, at least during the firing of our pilots. Nevertheless, the shooting was interrupted several times, which the Soviet side justified by the arrival of strategic aircraft from the Leningrad area, and by the alleged activity of the Swedish Air Force over the Baltic. During the first shootings in the early 1970s, we suspected our "comrades-in-arms" of the 16.IAD of maintaining air readiness to prevent our pilots from flying to Sweden. This would have been quite easy to detect on the radar screen used to control our pilots' firings. They simply didn't trust us, as usual.

Zone No.2 was 50 kilometers long, 8 kilometers wide in the south, and 45 kilometers wide in the north. The approach was on a 360° course via Ahlbeck Airport [Garz, today Heringsdorf], and the departure after the firing was a left turn to a 210° course. Combat firing of the missiles was possible in the 340-010° sector at altitudes of up to 20,000 m during subsonic or supersonic flight, day and night, in normal and difficult weather conditions. The minimum flight altitude above the clouds was to be 2,000 m, but this was not strictly adhered to. Firing was possible at the level of Peenemünde airfield and ended at the level of the town of Binz on Rügen. Fire control, including radio and radar support, was carried out from the airport in Damgarten. Incidentally, this also served as the main backup base. We flew to Damgarten as firing controllers the day before the firing began in a group of 3-4 officers with a complete live combat firing planning table. To secure the firing, it was also necessary to bring our own targets to Damgarten, which were then dropped by Soviet Il-28s. For example, in 1976, the 1st Airborne Transport Regiment from Mošnov transported a total of 10 M-6 bombs and 20 SAB-100/90 illumination bombs to the GDR by air."

Due to the demanding nature of such flights, it was necessary to first thoroughly prepare the selected fighter pilots in a "domestic" environment. This preparation was incorporated into the training schedule for each unit and consisted of ground and flight components. The pilots refreshed their knowledge of Russian radio communication, tactical and technical data on the RS-2US (radar-guided), R-3S and later R-13M (infrared-guided) missiles, emergency procedures in the event of engine failure, radio stations, radio compasses, etc. during 30 hours classes of theory.

Of course, they also had to study in detail the autonomous flight procedures at the firing range. Wet training in a swimming pool was also a necessity. During this training, pilots donned a complete altitude compensation suit, an orange Žilet-2M life jacket, and attempted to inflate an MLAS-1 life raft measuring 1890 x 960 mm, which was made of orange rubberized silk. Needless to say, climbing into a small, unstable boat in full gear was quite difficult, even in the calm waters of the pool.

In real conditions, the Baltic Sea would have awaited the pilots with a temperature of approximately 10°C and much rougher waves (the situation at sea was continuously monitored by the firing range, and shooting was cancelled when the waves became dangerous). Later, the Žilet-2M life jacket, which was certainly not very comfortable, was replaced by the newer ASž-58 model, which was gratefully accepted by the pilots. This life jacket, weighing approximately 2 kg, contained the following components: a carbon dioxide cartridge for inflation, 100 g of green-yellow water-soluble fluorescent paint in a separately sewn pocket, a signal light, and a mirror. In addition, KM-1 ejection seats (MiG-21PFM, MA, MF) also had a NAZ-7 emergency kit, which measured 390 x 380 x 50 mm and consisted of food supplies for 3 days, a compass, a flashlight, tools, a saw, medical supplies, matches, and ammunition. The total weight of this kit was approximately 6 kg. The NAZ-7 was placed together with the MLAS-1 boat in the pilot's parachute container at the bottom of the ejection seat. MiG-21F and PF aircraft with older SK-1 ejection seats could not carry this equipment due to the different seat design, and pilots had to rely on prompt assistance from rescue services in the event of ejection.

After completing ground training, flight training followed. The main focus was on flying along a designated route under normal weather conditions. These flights took place in MiG-21 (U, US, UM) "spárky" under NPP (normal weather conditions), and the instructor in the rear cabin simulated flying in clouds for the trainee pilot in the front cockpit by pulling down a curtain located above the headrest of the seat. This curtain completely blocked the pilot's view outside, but of course did not prevent him from seeing the instrument panel. The pilot had to rely solely on the "gauges," just as he would in a real situation. The conditions of these flights were quite harsh, but necessary. At an altitude of 50 meters after takeoff, the instructors usually pulled the "canopy" down and only raised it again in the final phase of the approach to landing. This training was generally very unpopular and often feared.

Of course, they also had to study in detail the autonomous flight procedures at the firing range. Wet training in a swimming pool was also a necessity. During this training, pilots donned a complete altitude compensation suit, an orange Žilet-2M life jacket, and attempted to inflate an MLAS-1 life raft measuring 1890 x 960 mm, which was made of orange rubberized silk. Needless to say, climbing into a small, unstable boat in full gear was quite difficult, even in the calm waters of the pool.

In real conditions, the Baltic Sea would have awaited the pilots with a temperature of approximately 10°C and much rougher waves (the situation at sea was continuously monitored by the firing range, and shooting was cancelled when the waves became dangerous). Later, the Žilet-2M life jacket, which was certainly not very comfortable, was replaced by the newer ASž-58 model, which was gratefully accepted by the pilots. This life jacket, weighing approximately 2 kg, contained the following components: a carbon dioxide cartridge for inflation, 100 g of green-yellow water-soluble fluorescent paint in a separately sewn pocket, a signal light, and a mirror. In addition, KM-1 ejection seats (MiG-21PFM, MA, MF) also had a NAZ-7 emergency kit, which measured 390 x 380 x 50 mm and consisted of food supplies for 3 days, a compass, a flashlight, tools, a saw, medical supplies, matches, and ammunition. The total weight of this kit was approximately 6 kg. The NAZ-7 was placed together with the MLAS-1 boat in the pilot's parachute container at the bottom of the ejection seat. MiG-21F and PF aircraft with older SK-1 ejection seats could not carry this equipment due to the different seat design, and pilots had to rely on prompt assistance from rescue services in the event of ejection.

After completing ground training, flight training followed. The main focus was on flying along a designated route under normal weather conditions. These flights took place in MiG-21 (U, US, UM) "spárky" under NPP (normal weather conditions), and the instructor in the rear cabin simulated flying in clouds for the trainee pilot in the front cockpit by pulling down a curtain located above the headrest of the seat. This curtain completely blocked the pilot's view outside, but of course did not prevent him from seeing the instrument panel. The pilot had to rely solely on the "gauges," just as he would in a real situation. The conditions of these flights were quite harsh, but necessary. At an altitude of 50 meters after takeoff, the instructors usually pulled the "canopy" down and only raised it again in the final phase of the approach to landing. This training was generally very unpopular and often feared.

The maximum range of the aircraft was also tested. The pilots flew in full gear, including life jackets, to Košice in Slovakia and back. For example, the 4th fighter wing from Pardubice flew the route Pardubice - Hradčany - Bechyně - Čáslav - Pieštany - Košice - Přerov - Pardubice at a speed of approx. 900 km/h at 10,000 m. During the return flight from Košice, the fighters simulated the final phase of missile launch. From a cruising altitude of 10,000 m, they descended to 8,800 m, increasing their speed to 1,100 km/h. The pilots then activated all relevant switches, performed a simulated launch, and then made a hard turn simulating leaving the target area.

Of course, training for interceptions and attacks on targets was also very important. These were trained in two basic variants. In the first, a two-seater MiG-21 flew at a speed of 500 km/h at an altitude of 14,300 m along a designated route. The command post guided individual fighters, who attacked the spárka at a speed of M 1.5-1.6 in an ascent from an altitude of 13,100 m. In the second case, the situation of an M-6 target bomb descending under a parachute, was simulated with a L-29 Delfín flying at an altitude of 6,000 and at a speed of 250-300 km/h on a predetermined route. The fighters were guided towards it at a speed of 1,000 km/h, which meant an approach speed of approximately 650-750 km/h! This is why the pilots nicknamed this exercise "fofrpřepad" (fast attack). The Delfín, which flew as a target, carried additional disc reflectors at the ends of the fuel tanks under its wings, which increased its visibility on the radar of the "twenty-ones."

The maximum range of the aircraft was also tested. The pilots flew in full gear, including life jackets, to Košice in Slovakia and back. For example, the 4th fighter wing from Pardubice flew the route Pardubice - Hradčany - Bechyně - Čáslav - Pieštany - Košice - Přerov - Pardubice at a speed of approx. 900 km/h at 10,000 m. During the return flight from Košice, the fighters simulated the final phase of missile launch. From a cruising altitude of 10,000 m, they descended to 8,800 m, increasing their speed to 1,100 km/h. The pilots then activated all relevant switches, performed a simulated launch, and then made a hard turn simulating leaving the target area.

Of course, training for interceptions and attacks on targets was also very important. These were trained in two basic variants. In the first, a two-seater MiG-21 flew at a speed of 500 km/h at an altitude of 14,300 m along a designated route. The command post guided individual fighters, who attacked the spárka at a speed of M 1.5-1.6 in an ascent from an altitude of 13,100 m. In the second case, the situation of an M-6 target bomb descending under a parachute, was simulated with a L-29 Delfín flying at an altitude of 6,000 and at a speed of 250-300 km/h on a predetermined route. The fighters were guided towards it at a speed of 1,000 km/h, which meant an approach speed of approximately 650-750 km/h! This is why the pilots nicknamed this exercise "fofrpřepad" (fast attack). The Delfín, which flew as a target, carried additional disc reflectors at the ends of the fuel tanks under its wings, which increased its visibility on the radar of the "twenty-ones."

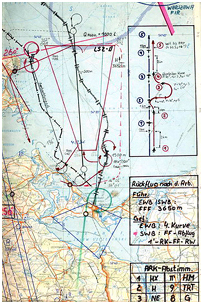

After these exercises, the first flight over the Baltic Sea took place. The selected pilot was first required to perform a navigation flight along the route to the firing range and back, but without live missiles. In exceptional cases, 1st class pilots did not fly this preliminary phase. In cloudless weather, the "twenty-ones" offered an interesting view of Germany, and after arriving at the Baltic Sea, it was sometimes possible to see the shores of Scandinavia during the turn. On the other hand, when flying in cloudy conditions, this flight was no walk in the park. Flights were most often conducted at two altitudes - 9,150 and 10,350 meters. After taking off from Žatec, the MiG-21s turned northeast towards Dresden. The first waypoint on the route was Grossenhain, followed by Brand - Finow - Angermünde, and then the fighters flew over the radio beacon to Ahlbeck, where the maneuver before the missile launch began. After firing, they turned around and continued on to Brandenburg - Neuruppin - Altes Lager - Falkenberg, and then the MiGs, thirstily "guzzling" their last few hundred liters of fuel, headed for their home base in Žatec. Throughout the flight, only the necessary radio communication took place, and of course in Russian.

The second flight was conducted by two fighter jets. The lead aircraft carried a modified RM-3V missile. It was an original R-3S missile stripped of its warhead and guidance system, and fitted with a modified engine to achieve lower speeds. The wingman flew with a standard R-3S. Both aircraft increased their speed to 1,000 km/h above Ahlbeck and adjusted the distance between them to 500 m with an altitude difference of 100-200 m. On instructions from ground control, the lead aircraft climbed to a 10- to 15-degree angle and fired the RM-3V. He then rolled down, and the wingman waited for a signal from the infrared-guided R-3S sensor, which confirmed the acquisition of the target in his headset. He then fired and turned to follow the lead aircraft without observing the result of the firing. However, firing the RM-3V target missile also carried certain risks. The modified missile's engine emitted more smoke, and there was a risk that these gases could be drawn into the carrier aircraft, potentially causing engine surge and failure. In practice, this occured several times, fortunately without fatal consequences. On June 12, 1989, a pilot of the 11.slp encountered this situation aboard his MiG-21PFM. He handled the emergency brillantly and brought the "twenty-one" back to Žatec safely.

The same problem was encountered during the last [or one of the last? (4)] firing exercises over the East German Baltic Sea on June 6, 1990, by First Lieutenant Zdeněk Svoboda, a third-class pilot of the 5.slp, flying a MiG-21F. Immediately after firing an RM-3V over the sea, the young pilot noticed irregular engine operation. He looked at the engine tachometer and was horrified. The needle was fluctuating at 50%! Even though he was far above the sea, he remained calm. He shut down the engine and adjusted the speed to 500 km/h. With his left hand, he automatically moved the POM (throttle) to idle while turning the MiG back over land. He reported his emergency situation to the command post and simultaneously pressed the engine restart button. While still struggling to revive and save the aircraft, his announcement alerted the Soviet rescue service. Mi-14 rescue helicopters took off from Peenemünde [or rather from Parow, the homebase of the MHG-18 - Soviet SAR Mi-8s were also supposed to be deployed at Damgarten], and patrol boats also received orders to set sail. At 6,000 meters, the situation suddenly resolved itself. The engine slowly but surely reached normal operating speed, and after a while, First Lieutenant Svoboda could confidently report that it was running smoothly. At that moment, he was still flying over the sea... He managed to return to Líně without incident, but the dramatic moments over the Baltic Sea certainly did not allow him to sleep soundly that night.

The second flight was conducted by two fighter jets. The lead aircraft carried a modified RM-3V missile. It was an original R-3S missile stripped of its warhead and guidance system, and fitted with a modified engine to achieve lower speeds. The wingman flew with a standard R-3S. Both aircraft increased their speed to 1,000 km/h above Ahlbeck and adjusted the distance between them to 500 m with an altitude difference of 100-200 m. On instructions from ground control, the lead aircraft climbed to a 10- to 15-degree angle and fired the RM-3V. He then rolled down, and the wingman waited for a signal from the infrared-guided R-3S sensor, which confirmed the acquisition of the target in his headset. He then fired and turned to follow the lead aircraft without observing the result of the firing. However, firing the RM-3V target missile also carried certain risks. The modified missile's engine emitted more smoke, and there was a risk that these gases could be drawn into the carrier aircraft, potentially causing engine surge and failure. In practice, this occured several times, fortunately without fatal consequences. On June 12, 1989, a pilot of the 11.slp encountered this situation aboard his MiG-21PFM. He handled the emergency brillantly and brought the "twenty-one" back to Žatec safely.

The same problem was encountered during the last [or one of the last? (4)] firing exercises over the East German Baltic Sea on June 6, 1990, by First Lieutenant Zdeněk Svoboda, a third-class pilot of the 5.slp, flying a MiG-21F. Immediately after firing an RM-3V over the sea, the young pilot noticed irregular engine operation. He looked at the engine tachometer and was horrified. The needle was fluctuating at 50%! Even though he was far above the sea, he remained calm. He shut down the engine and adjusted the speed to 500 km/h. With his left hand, he automatically moved the POM (throttle) to idle while turning the MiG back over land. He reported his emergency situation to the command post and simultaneously pressed the engine restart button. While still struggling to revive and save the aircraft, his announcement alerted the Soviet rescue service. Mi-14 rescue helicopters took off from Peenemünde [or rather from Parow, the homebase of the MHG-18 - Soviet SAR Mi-8s were also supposed to be deployed at Damgarten], and patrol boats also received orders to set sail. At 6,000 meters, the situation suddenly resolved itself. The engine slowly but surely reached normal operating speed, and after a while, First Lieutenant Svoboda could confidently report that it was running smoothly. At that moment, he was still flying over the sea... He managed to return to Líně without incident, but the dramatic moments over the Baltic Sea certainly did not allow him to sleep soundly that night.

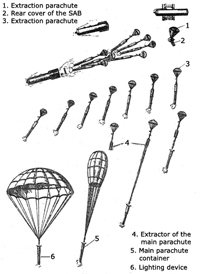

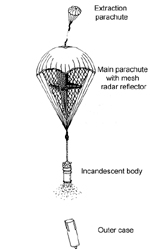

During the third flight, the pilots fired R-3S or RS-2US missiles at an M-6 target-bomb. Identical in appearance to other 100 kg bombs, it concealed a heat source beneath its casing, mounted under a parachute, instead of explosives. After release, a small extraction parachute opened, pulling up the main canopy which had a surface area of 36 m2. The contents were ejected from the casing by dynamic force, and the pyrotechnic device started to burn suspended below the parachute, attached to a 9-meter rope. The light of the flame was often visible from Berlin [!?], while pilots using their RP-21 radars could catch the target at a maximum distance of 20 km. In order to increase the radar signature of the target, a four-sided pyramid-shaped reflector made of metallized fabric was mounted between the intertwined cords of the parachute. The echo on the radar tube in the cockpit of the "twenty-ones" replicated a target approximately the size of a medium bomber. Meanwhile, the small extraction parachute and the bomb body itself continued to fall freely towards the surface of the Pomeranian Bay. The parachute with the burner descended at a speed of approximately 5-8 m/s. These bombs were initially dropped by the Soviets from Il-28 aircraft flying in circles above the firing range at an altitude of 10,000 m. However, from 1982 onwards, due to poor communication with their crews, this role was assumed by MiG-23BNs of the 28.sbolp from Čáslav.

The "Béenka" were flying over the Baltic with three drop tanks and a pair of M-6 target-bombs. Within the target area of the firing range, the MiG-23BN flew at a speed of 800 km/h in the opposite direction at a higher altitude than the approaching MiG-21s, systematically dropping a target ahead of them. In the second half of the 1980s, the MiG-21MFs took over this mission themselves. The command post guided two or three pairs of fighters to one descending target. When firing at the M-6, the pilots flew at a sufficient distance of approximately 25 km apart and only one aircraft fired at a time. The distance specified for launching missiles was 5 to 8km, and the maximum possible limit before the exit from the run was set by regulation at 4 km.

The fact that underestimating and exceeding this distance was inadvisable is clearly demonstrated by the incident of May 28, 1983, when MiG-21PFM n°7115 from the 11.slp in Žatec was heading to a live-fire exercise. At 22:40, the experienced pilot, Lt. Col. Vladimír Daněk took off in ZPPN conditions. The aircraft was carrying RS-2US radar-guided missiles, among the most difficult to operate while respecting the maximum limit distance. These missiles, guided along the radar beam, required tracking the target almost until the moment of impact. In the event of a premature roll-off from the beam, the missile would deviate and, in the vast majority of cases, missed its target. This is why pilots sometimes took risks and knowingly exceeded this 4km limit to complete the task to ensure the success of their mission.

During the third flight, the pilots fired R-3S or RS-2US missiles at an M-6 target-bomb. Identical in appearance to other 100 kg bombs, it concealed a heat source beneath its casing, mounted under a parachute, instead of explosives. After release, a small extraction parachute opened, pulling up the main canopy which had a surface area of 36 m2. The contents were ejected from the casing by dynamic force, and the pyrotechnic device started to burn suspended below the parachute, attached to a 9-meter rope. The light of the flame was often visible from Berlin [!?], while pilots using their RP-21 radars could catch the target at a maximum distance of 20 km. In order to increase the radar signature of the target, a four-sided pyramid-shaped reflector made of metallized fabric was mounted between the intertwined cords of the parachute. The echo on the radar tube in the cockpit of the "twenty-ones" replicated a target approximately the size of a medium bomber. Meanwhile, the small extraction parachute and the bomb body itself continued to fall freely towards the surface of the Pomeranian Bay. The parachute with the burner descended at a speed of approximately 5-8 m/s. These bombs were initially dropped by the Soviets from Il-28 aircraft flying in circles above the firing range at an altitude of 10,000 m. However, from 1982 onwards, due to poor communication with their crews, this role was assumed by MiG-23BNs of the 28.sbolp from Čáslav.

The "Béenka" were flying over the Baltic with three drop tanks and a pair of M-6 target-bombs. Within the target area of the firing range, the MiG-23BN flew at a speed of 800 km/h in the opposite direction at a higher altitude than the approaching MiG-21s, systematically dropping a target ahead of them. In the second half of the 1980s, the MiG-21MFs took over this mission themselves. The command post guided two or three pairs of fighters to one descending target. When firing at the M-6, the pilots flew at a sufficient distance of approximately 25 km apart and only one aircraft fired at a time. The distance specified for launching missiles was 5 to 8km, and the maximum possible limit before the exit from the run was set by regulation at 4 km.

The fact that underestimating and exceeding this distance was inadvisable is clearly demonstrated by the incident of May 28, 1983, when MiG-21PFM n°7115 from the 11.slp in Žatec was heading to a live-fire exercise. At 22:40, the experienced pilot, Lt. Col. Vladimír Daněk took off in ZPPN conditions. The aircraft was carrying RS-2US radar-guided missiles, among the most difficult to operate while respecting the maximum limit distance. These missiles, guided along the radar beam, required tracking the target almost until the moment of impact. In the event of a premature roll-off from the beam, the missile would deviate and, in the vast majority of cases, missed its target. This is why pilots sometimes took risks and knowingly exceeded this 4km limit to complete the task to ensure the success of their mission.

Lt. Col. Daněk also exceeded this distance during a night firing exercise. He fired two missiles in a gentle climb and tracked them for approximately 6 to 8 seconds. Then he initiated a sharp turn at a speed of 1,000 km/h and an altitude of 7,500 m back above the mainland. Suddenly, a drop in cabin noise surprised him, a sign of trouble. The pilot quickly checked the instruments and noted a decrease in engine RPM and a low exhaust gas temperature. This indicated an engine failure. He then aligned the MiG on a heading of 240 degrees and reported the problem to the command post. He attempted to restart the R-11 reactor three times without success. At 3,000 m the fighter was swallowed by clouds and the situation became critical. The MiG-21 was losing about 30 m/s! At an altitude of 2,000 m, Lt. Col. Daněk received the order to eject, which he confirmed; bowever, he hesitated for a moment. He did not want to eject over the sea.

The "twenty-one" suddenly emerged from the clouds and the pilot saw lights below him. He was over land! At 1,700 meters, he turned the plane into the darkness, leaned back in his seat and, pulling the red handles, ejected from the stricken MiG. Moments later, the KM-1 seat detached, and the pilot found himself under his parachute. At that precise moment, only 25 minutes had passed since takeoff from Žatec. However, Lt. Col. Daněk's adventure was not far from over. He landed directly on the greenhouse of the Greifswald Botanical Garden and crashed through the glass, fortunately without serious injury. After a while, he realized where he was and that the building was locked. Maintaining his composure, he climbed out using his parachute straps and made his way to the nearest house to signal his presence to the German security forces. His aircraft crashed in a cornfield 3 km NW of the town, causing only minor damage to the crops themselves. The canopy shattered in a deserted street in Greifswald, while the seat was found on the roof of a house. The remaining wreckage of the "twenty-one", destroyed by fire after the impact, was transported to the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic for examination. After thorough analyses, the cause of the engine failure was determined. The aircraft sucked the small extraction parachute of an M-6 target that

was carried by the wind toward the continent, in the direction of approaching fighters. This incredible coincidence, with a probability of perhaps one in a million, cost a total of 3,919,000 CZK (> Link to the story with pictures in Czech language).

However, most of the problems encountered during live-fire missions in the Baltic zone were due to various types of malfunctions. These ranged from "banal" failures of control instruments to very serious malfunctions, often bordering on accidents and, in the worst cases, catastrophe. For example, on May 27, 1983, pilots of the 8.slp, were detached from Brno with their MiG-21PF to Žatec for a planned live-fire exercise. Capt. Jaroslav Adámek piloting "Péefca" [PF] n°0306 experienced a sudden nose drop during takeoff, accompanied by a strong yaw to the right. The pilot assessed this extraordinary situation as an engine failure and a burst tire on the right main landing gear, and attempted to abort the takeoff. The MiG, filled to the brim with fuel and carrying a 490-liter fuel tank under the fuselage and missiles, already resembled an uncontrollable steamroller rolling down a hill. The aircraft left the runway at a speed of approximately 300 km/h and headed towards the embankment bordering the airfield. The pilot, aware of the imminent danger, reacted by retracting the landing gear - a desperate measure, but at that moment, he had no other choice. The MiG-21 crashed onto its under-fuselage fuel tank, its wings simultaneously scraping the ground. The aircraft slid almost to the embankment by inertia, but miraculously, it did not explode. The pilot, in shock, left the cockpit, and rescue teams took over. The subsequent investigation revealed that at a critical moment, a malfunction had occurred in the flap control system, causing the flaps to retract unexpectedly.

Lt. Col. Daněk also exceeded this distance during a night firing exercise. He fired two missiles in a gentle climb and tracked them for approximately 6 to 8 seconds. Then he initiated a sharp turn at a speed of 1,000 km/h and an altitude of 7,500 m back above the mainland. Suddenly, a drop in cabin noise surprised him, a sign of trouble. The pilot quickly checked the instruments and noted a decrease in engine RPM and a low exhaust gas temperature. This indicated an engine failure. He then aligned the MiG on a heading of 240 degrees and reported the problem to the command post. He attempted to restart the R-11 reactor three times without success. At 3,000 m the fighter was swallowed by clouds and the situation became critical. The MiG-21 was losing about 30 m/s! At an altitude of 2,000 m, Lt. Col. Daněk received the order to eject, which he confirmed; bowever, he hesitated for a moment. He did not want to eject over the sea.

The "twenty-one" suddenly emerged from the clouds and the pilot saw lights below him. He was over land! At 1,700 meters, he turned the plane into the darkness, leaned back in his seat and, pulling the red handles, ejected from the stricken MiG. Moments later, the KM-1 seat detached, and the pilot found himself under his parachute. At that precise moment, only 25 minutes had passed since takeoff from Žatec. However, Lt. Col. Daněk's adventure was not far from over. He landed directly on the greenhouse of the Greifswald Botanical Garden and crashed through the glass, fortunately without serious injury. After a while, he realized where he was and that the building was locked. Maintaining his composure, he climbed out using his parachute straps and made his way to the nearest house to signal his presence to the German security forces. His aircraft crashed in a cornfield 3 km NW of the town, causing only minor damage to the crops themselves. The canopy shattered in a deserted street in Greifswald, while the seat was found on the roof of a house. The remaining wreckage of the "twenty-one", destroyed by fire after the impact, was transported to the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic for examination. After thorough analyses, the cause of the engine failure was determined. The aircraft sucked the small extraction parachute of an M-6 target that

was carried by the wind toward the continent, in the direction of approaching fighters. This incredible coincidence, with a probability of perhaps one in a million, cost a total of 3,919,000 CZK (> Link to the story with pictures in Czech language).

However, most of the problems encountered during live-fire missions in the Baltic zone were due to various types of malfunctions. These ranged from "banal" failures of control instruments to very serious malfunctions, often bordering on accidents and, in the worst cases, catastrophe. For example, on May 27, 1983, pilots of the 8.slp, were detached from Brno with their MiG-21PF to Žatec for a planned live-fire exercise. Capt. Jaroslav Adámek piloting "Péefca" [PF] n°0306 experienced a sudden nose drop during takeoff, accompanied by a strong yaw to the right. The pilot assessed this extraordinary situation as an engine failure and a burst tire on the right main landing gear, and attempted to abort the takeoff. The MiG, filled to the brim with fuel and carrying a 490-liter fuel tank under the fuselage and missiles, already resembled an uncontrollable steamroller rolling down a hill. The aircraft left the runway at a speed of approximately 300 km/h and headed towards the embankment bordering the airfield. The pilot, aware of the imminent danger, reacted by retracting the landing gear - a desperate measure, but at that moment, he had no other choice. The MiG-21 crashed onto its under-fuselage fuel tank, its wings simultaneously scraping the ground. The aircraft slid almost to the embankment by inertia, but miraculously, it did not explode. The pilot, in shock, left the cockpit, and rescue teams took over. The subsequent investigation revealed that at a critical moment, a malfunction had occurred in the flap control system, causing the flaps to retract unexpectedly.

Another pilot flying a MiG-21MF had a minimum oil pressure warning light after the launch of the missiles. He immediately checked the instrument and found the needle oscillating between the minimum and maximum readings. This was likely a fluid leak, and the risk of imminent engine failure was real. The pilot therefore had to request an emergency landing at an alternate airfield in East Germany. He set his radio compass to the signal of the beacon at Damgarten Air Base and reported his problem to the command post. He was then ordered to land at the aforementioned airfield. He continued to monitor the oil pressure gauge, and at an altitude of approximately 7,000 meters, the light suddenly went out. He cautiously increased the throttle, but the light did not come back on. He immediately reported the change in situation and headed for Neuruppin. He brought the aircraft back without further incident. After landing, technicians discovered a faulty sensor located in the oil separator, which had triggered the alarm.

The radio of different aircraft went down on several occasions after takeoff. This, of course, necessitated a return flight, as it was impossible to launch the missiles without reporting to the firing range command post. The situation worsened when multiple failures occurred.This is what Captain Oldřich Valehrach, deputy commander of the 3rd Squadron of the 11th Fighter Aviation Regiment, experienced. In June 1985, he was flying over the Baltic Sea in a MiG-21MF carrying two M-6 targets to be dropped for his colleagues, who were then supposed to attack them. The flight took place in ZPPD conditions and the pilot had to rely on the radio compass, on-board clock and, of course, the gyrocompass. Once in the firing range, he discovered that the radio compass was out of order. He reported the malfunction, however, following instructions from the command post, he nevertheless proceeded to drop the targets. He released them at an altitude of 9,450 m on the return flight. However, after 5 minutes of flight, he experienced a loss of communication. At that moment, the situation began to worsen. The pilot immediately activated the distress signal, which replicates the aircraft's radar marking, and the backup converter. Unfortunately, he was unable to restore the instrument functionality. He then compared his last known position and continued on his way, navigating using his watch and compass. After some time, he began to descend, as he was still flying in the clouds and wanted to orient himself using the terrain. He took a risk, but luck was on his side. Suddenly, a break in the clouds appeared, and he climbed to an altitude of 500 meters. Spotting a large city in the distance, he mistook it for Prague and headed for České Budějovice. However, the cloud cover relentlessly pushed him back down, and he could no longer recognize the landscape below. Flying at low altitude significantly increased fuel consumption, leaving him no time for further options.

Nevertheless, the pilot cold-bloodedly turned the "Emefka" 180 degrees, and announced that he would land in Kbely or Ruzyne. Visibility was already decreasing, and upon approaching "Prague," the minimum fuel remaining warning light was already on. After a brief holding pattern, he landed immediately on the runway and, having left the area, headed towards the exit of the civilian terminal so as not to disrupt traffic. The sign "Flughafen Dresden" shone brightly on the building's facade. The surprise was mutual, as Dresden air traffic control was clearly not used to this type of event. Ultimately, everything ended without major incident. Air traffic was not disrupted, and the young pilot, displaying remarkable composure, managed to contact the commander of the 11.slp in Žatec.

Another pilot flying a MiG-21MF had a minimum oil pressure warning light after the launch of the missiles. He immediately checked the instrument and found the needle oscillating between the minimum and maximum readings. This was likely a fluid leak, and the risk of imminent engine failure was real. The pilot therefore had to request an emergency landing at an alternate airfield in East Germany. He set his radio compass to the signal of the beacon at Damgarten Air Base and reported his problem to the command post. He was then ordered to land at the aforementioned airfield. He continued to monitor the oil pressure gauge, and at an altitude of approximately 7,000 meters, the light suddenly went out. He cautiously increased the throttle, but the light did not come back on. He immediately reported the change in situation and headed for Neuruppin. He brought the aircraft back without further incident. After landing, technicians discovered a faulty sensor located in the oil separator, which had triggered the alarm.

The radio of different aircraft went down on several occasions after takeoff. This, of course, necessitated a return flight, as it was impossible to launch the missiles without reporting to the firing range command post. The situation worsened when multiple failures occurred.This is what Captain Oldřich Valehrach, deputy commander of the 3rd Squadron of the 11th Fighter Aviation Regiment, experienced. In June 1985, he was flying over the Baltic Sea in a MiG-21MF carrying two M-6 targets to be dropped for his colleagues, who were then supposed to attack them. The flight took place in ZPPD conditions and the pilot had to rely on the radio compass, on-board clock and, of course, the gyrocompass. Once in the firing range, he discovered that the radio compass was out of order. He reported the malfunction, however, following instructions from the command post, he nevertheless proceeded to drop the targets. He released them at an altitude of 9,450 m on the return flight. However, after 5 minutes of flight, he experienced a loss of communication. At that moment, the situation began to worsen. The pilot immediately activated the distress signal, which replicates the aircraft's radar marking, and the backup converter. Unfortunately, he was unable to restore the instrument functionality. He then compared his last known position and continued on his way, navigating using his watch and compass. After some time, he began to descend, as he was still flying in the clouds and wanted to orient himself using the terrain. He took a risk, but luck was on his side. Suddenly, a break in the clouds appeared, and he climbed to an altitude of 500 meters. Spotting a large city in the distance, he mistook it for Prague and headed for České Budějovice. However, the cloud cover relentlessly pushed him back down, and he could no longer recognize the landscape below. Flying at low altitude significantly increased fuel consumption, leaving him no time for further options.

Nevertheless, the pilot cold-bloodedly turned the "Emefka" 180 degrees, and announced that he would land in Kbely or Ruzyne. Visibility was already decreasing, and upon approaching "Prague," the minimum fuel remaining warning light was already on. After a brief holding pattern, he landed immediately on the runway and, having left the area, headed towards the exit of the civilian terminal so as not to disrupt traffic. The sign "Flughafen Dresden" shone brightly on the building's facade. The surprise was mutual, as Dresden air traffic control was clearly not used to this type of event. Ultimately, everything ended without major incident. Air traffic was not disrupted, and the young pilot, displaying remarkable composure, managed to contact the commander of the 11.slp in Žatec.

Monitoring the actual fuel level against the calculated level written on the navigation chart at relevant waypoints was a major concern for pilots. This monitoring was crucial, because even under normal conditions, aircraft frequently landed with warning lights flashing, constantly signaling a drop in fuel level. A MiG-21PFM pilot encountered a particularly unpleasant situation in May 1979. He carried out live-firing over the Baltic Sea in fine weather, perhaps even enjoying the magnificent scenery. However, on his return, about 30 km from his base, the "450 l remaining" warning light came on. The fuel gauge, set before the flight according to the amount of fuel on board, displayed double that amount - 900 l. He immediately signaled the discrepancy between the two instruments and switched to economic flight mode. His eyes then searched impatiently for the home runway. After landing, ground personnel immediately began inspecting his aircraft. The cause was quickly identified. The maintenance technician servicing the aircraft had forgotten to connect the compressed air supply to the fuel tank fixed under the fuselage, thus preventing the transfer of fuel to the main fuselage tanks.

Another unusual malfunction occurred to an experienced pilot of the 1st fighter division (1.sld). During descent on his return flight from the Baltic, at an altitude of approximately 5,000 m, he noticed anormal noises coming from the nose of his MiG-21MF. He immediately suspected a malfunction of the air intake cone, which automatically retracted and extended depending on airspeed to supply the engine with the necessary amount of air. Unfortunately, at that precise moment, the airflow became insufficient. The "twenty-one" had a manual control for this cone in such situations, but even after its use, the situation did not improve. The risk of engine "pumping" and stalling was real. The pilot reported the malfunction and maintained a reserve altitude while keeping the engine at minimum power. However, this malfunction brought with it another complication. Due to the low engine speed, the unit responsible for blowing the boundary layer on the flaps (SPS), which allowed the aircraft to be better controlled at landing speeds of around 300 km/h, failed. The fighter therefore began its final approach at 360 km/h, which was an increase of approximately 60 km/h above normal. Fortunately, the landing was spot on and the aircraft touched down safely. For an experienced but infrequently flying pilot, this situation was not at all easy. A subsequent inspection revealed a defect in the valve of the hydraulic jack, which ensured the change in the position of the cone.

Another unusual malfunction occurred to an experienced pilot of the 1st fighter division (1.sld). During descent on his return flight from the Baltic, at an altitude of approximately 5,000 m, he noticed anormal noises coming from the nose of his MiG-21MF. He immediately suspected a malfunction of the air intake cone, which automatically retracted and extended depending on airspeed to supply the engine with the necessary amount of air. Unfortunately, at that precise moment, the airflow became insufficient. The "twenty-one" had a manual control for this cone in such situations, but even after its use, the situation did not improve. The risk of engine "pumping" and stalling was real. The pilot reported the malfunction and maintained a reserve altitude while keeping the engine at minimum power. However, this malfunction brought with it another complication. Due to the low engine speed, the unit responsible for blowing the boundary layer on the flaps (SPS), which allowed the aircraft to be better controlled at landing speeds of around 300 km/h, failed. The fighter therefore began its final approach at 360 km/h, which was an increase of approximately 60 km/h above normal. Fortunately, the landing was spot on and the aircraft touched down safely. For an experienced but infrequently flying pilot, this situation was not at all easy. A subsequent inspection revealed a defect in the valve of the hydraulic jack, which ensured the change in the position of the cone.

An interesting experiment took place, on June 10, 1989 within the 11.slp of Žatec. An R-60 missile was tested on a MiG-21PFM equipped with a P-62-1M (APU-60) adapter, and a subsequent launch was then conducted in the Baltic zone. To my knowledge, this is the only documented instance of the use and firing of the R-60 air-to-air missile from a MiG-21PFM of our Air Force. Of course, I cannot rule out other cases, but the R-60 was never integrated into the standard equipment of the MiG-21PFM within our Air Force. However, photographs of East German Air Force MiG-21PFMs, equipped with at least P-62-1M adapters, do exist.

During the same Live Combat Fire (OBS) exercise, an extraordinary event occured on June 12, 1989, when three MiG-21PFM (n°4405, 4406, and 4411) from the 2nd squadron of the 11.slp, returned from the Baltic Sea to Žatec with RS-2US missiles still suspended under their wings. The cause of this failure was apparently an error made by the armorers when they mounted the missiles on the aircraft.

Of course, it wasn't just the "twenty-ones" that flew over the Baltic. Starting in 1979, the "boxes" began to appear in the region - that is, the MiG-23MF of the 1.slp from České Budějovice, which were later transferred to the 11.slp in Žatec. A little later, an improved version, the ML, also appeared. For example, at the end of May 1983, MiG-23ML of the 1.slp were operating in the "Baltic zone." They did not fly from their home base in České Budějovice, but flew from Merseburg in the GDR for this purpose. As part of preparations for deploying the "ML" for home air defence (HS PVOS), pilots, primarily from the 2nd squadron, conducted 25 missile firings. The "twenty-threes" fired exclusively R-3S and R-13M IR missiles. The use of their primary armament, the R-23 missiles with a usable range of up to 40 km, was not possible due to the size of the firing range; these missiles were therefore only fired in Astrakhan. The MiG-23 pilots also experienced two engine failures during the firing exercises, but the aircraft were always able to return to base after the engine restarted.

Another interesting chapter of the "Zóna Balt" history concerns the use of R-3S missiles on L-39ZA aircraft. These aircraft were delivered to the 30.sbolp at Hradec Králové in 1982 as a temporary replacement for the decommissioned MiG-15bis SB. From 1984 unward, they were integrated into fighter regiments as part of the PVOS alert system against low and slow-moving targets. Their armament also included R-3S infrared missiles (although these were not used in actual alerts). In late May 1988, a squadron of four Albatrosses flew to Damgarten. A MiG-23 fighter regiement was based here [MiG-23MLD 773.IAP], and the local pilots watched the L-39ZAs armed with missiles with curiosity. The first firing took place on June 1, 1988. The Albatros pilots climbed to 7,000 m, from where they began to descend and increased their speed to 700 km/h. At that moment, M-6 targets appeared in front of them, emitting a bright light. All the pilots fired and agreed that nothing unusual had occured with the aircraft during the firing. However, the next group encountered a significant surprise. After the missile was fired, the aircraft banked sharply to the side of the mounted missile, which the pilots corrected by pushing the rudder pedal fully to the opposite side. Simultaneously, a slight acceleration of the aircraft was also recorded. The same situation occurred for all the aircraft.

Since none of the pilots had seen a missile depart from under the wing of his aircraft, the reasons for the incident began to become clearer. After landing, the cause was quickly identified. The chief weapons engineer had mistakenly given incorrect instructions for adjusting the APU-13 adapters to which the R-3S were mounted. Even the thrust of the activated rocket motor proved insufficient to release the missile from its adapter at the moment of launch. These missiles continued to be used for training purposes for a long time afterwards.

Another interesting chapter of the "Zóna Balt" history concerns the use of R-3S missiles on L-39ZA aircraft. These aircraft were delivered to the 30.sbolp at Hradec Králové in 1982 as a temporary replacement for the decommissioned MiG-15bis SB. From 1984 unward, they were integrated into fighter regiments as part of the PVOS alert system against low and slow-moving targets. Their armament also included R-3S infrared missiles (although these were not used in actual alerts). In late May 1988, a squadron of four Albatrosses flew to Damgarten. A MiG-23 fighter regiement was based here [MiG-23MLD 773.IAP], and the local pilots watched the L-39ZAs armed with missiles with curiosity. The first firing took place on June 1, 1988. The Albatros pilots climbed to 7,000 m, from where they began to descend and increased their speed to 700 km/h. At that moment, M-6 targets appeared in front of them, emitting a bright light. All the pilots fired and agreed that nothing unusual had occured with the aircraft during the firing. However, the next group encountered a significant surprise. After the missile was fired, the aircraft banked sharply to the side of the mounted missile, which the pilots corrected by pushing the rudder pedal fully to the opposite side. Simultaneously, a slight acceleration of the aircraft was also recorded. The same situation occurred for all the aircraft.

Since none of the pilots had seen a missile depart from under the wing of his aircraft, the reasons for the incident began to become clearer. After landing, the cause was quickly identified. The chief weapons engineer had mistakenly given incorrect instructions for adjusting the APU-13 adapters to which the R-3S were mounted. Even the thrust of the activated rocket motor proved insufficient to release the missile from its adapter at the moment of launch. These missiles continued to be used for training purposes for a long time afterwards.

In conclusion, we will attempt a brief statistical assessment. Unfortunately, the destruction of the records relating to missile launches over the eastern Baltic Sea prevents us from determining the exact number of these flights. Knowing that this number fluctuated between 120 and 150 launches per year, we can state with certainty that more than 2,000 R-3S, R-13M, and RS-2US missiles were fired in total.

Raketa odpálena!

> Link to part 1

> Link to part 2

> Link to part 3

> Link to part 4

notes

(1)

The Hungarian People's Army Air Force did not use the East German air-to-air firing range. However, Soviet units based in Hungary did so.

Instead, the Hungarians used the Astrakhan (USSR) and Ustka (Poland) firing ranges. Nevertheless, Su-22M3/UM3 of the 101st

Reconnaissance Aviation Squadron from Taszár were deployed at Laage in August 1987 and they used the range off Peenemünde for anti ship

bombing missions. It was a return visit after the JBG-77 went to Taszár in July/August.

(2)

Central Air Force Training Ground in Ustka (>Link).

(3)

Aleksey Nikolayevich Katrich was awarded the order of Hero of the Soviet Union for ramming and shooting down a Do 215 with his MiG-3 on

August 11, 1941

(> Link).

(4) The LSZ II attracted considerable interest among ufologists on August 24, 1990 when numerous witnesses observed SAB bombs in the evening.

A missile launch is even visible in a video from that time. It is generally accepted that this was the last Czechoslovakian live firing session.

However, no known document confirms this. In any case, the Su-25BMs of the 65th OBAE departed Damgarten for Demmin in October 1990,

thus confirming the end of LSZ II.

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |