That on its own would have been bad

enough, but we were at the same time photographing equipment of intelligence value that the Soviets and East Germans would have preferred

to keep secret. In addition, the seating arrangements made navigation very difficult and there was always the chance of getting lost.

That and the prospect of an engine failure were never very far from anybody's thoughts since the repercussions could well have led to what we

referred to as "The long Russian course". However, the groundcrew at RAF Gatow were, I am pleased to say, dedicated to the servicing of the Chipmunks

since they were only too well aware that it was vitally important that none of the aircraft should have to carry out an emergency forced landing when they

were on the wrong side of the Wall, particularly since many of the intelligence targets were some distance from Gatow and well to the east of East Berlin.

The Soviets were not at all happy with these aircraft flying overhead, one of the reasons being that we were not the only Allied Power collecting

intelligence from the air. Both the French from Tegel and the Americans from Templehof were also flying in the BCZ, but BRIXMIS was the only

Allied Mission that actually had complete control of its own operation, carrying out both the flying and the photography. The French Mission did

their own photography but were flown by other than their own personnel. The American aircraft however was operated by a completely different

intelligence agency. It was therefore not always possible to co-ordinate their activities to the same degree as we did on the ground. Ground co-ordination

was achieved by weekly Tri-Mission meetings of the operations staff where great care was taken to ensure that there were no unexpected and

embarrassing meetings close to any installations in the GDR.

That on its own would have been bad

enough, but we were at the same time photographing equipment of intelligence value that the Soviets and East Germans would have preferred

to keep secret. In addition, the seating arrangements made navigation very difficult and there was always the chance of getting lost.

That and the prospect of an engine failure were never very far from anybody's thoughts since the repercussions could well have led to what we

referred to as "The long Russian course". However, the groundcrew at RAF Gatow were, I am pleased to say, dedicated to the servicing of the Chipmunks

since they were only too well aware that it was vitally important that none of the aircraft should have to carry out an emergency forced landing when they

were on the wrong side of the Wall, particularly since many of the intelligence targets were some distance from Gatow and well to the east of East Berlin.

The Soviets were not at all happy with these aircraft flying overhead, one of the reasons being that we were not the only Allied Power collecting

intelligence from the air. Both the French from Tegel and the Americans from Templehof were also flying in the BCZ, but BRIXMIS was the only

Allied Mission that actually had complete control of its own operation, carrying out both the flying and the photography. The French Mission did

their own photography but were flown by other than their own personnel. The American aircraft however was operated by a completely different

intelligence agency. It was therefore not always possible to co-ordinate their activities to the same degree as we did on the ground. Ground co-ordination

was achieved by weekly Tri-Mission meetings of the operations staff where great care was taken to ensure that there were no unexpected and

embarrassing meetings close to any installations in the GDR.

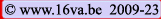

Antennes d'un système de communication troposphérique à relais multiples. © BRIXMIS.

Antennes d'un système de communication troposphérique à relais multiples. © BRIXMIS.

Antennas of a multihop troposcatter relay communication system. © BRIXMIS.

In fact it was not unusual to see the American aircraft making for the

same target as ourselves. We would normally try not to play follow-my-leader over an important intelligence target as that really did attract

unwelcome attention. Not only that, but aircraft orbiting the same target at the same time in opposite directions, as happened on more than one

occasion, was certainly not conducive to flight safety. The occasional head-on confrontation required a sharp look-out from the photographer at a time

when he had other things on his mind. Some attempts were made at vertical separation, but unfortunately they never amounted to anything.

The problem was that this operation was not reciprocated by SOXMIS in West Germany, because the Soviet Military Mission at Bunde was wholly

a ground operation. It was purely good fortune arising from the Four Power Agreement on Berlin that had allowed the Allied Powers to fly training and

transport aircraft into the three Allied airfields. The Agreement stated that these flights were 'solely for the reinforcement of the Garrison' and had to

originate in West Germany. If flights did not meet this requirement, the Soviet controllers in BASC felt obliged to stamp the flight request card

"Safety of Flight Not Guaranteed", an action that would most decidedly have perturbed passengers on British Airways flights into West Berlin that

originated in the UK, had they known about it. Naturally, the Chipmunk flights were definitely not "Safety of Flight Guaranteed".

The reason for this Agreement was the fact that West Berlin lay 100 miles inside what was the Soviet Zone of Occupation, an arrangement that

the Soviets must have regretted when it came to the Berlin Airlift. This then was the background to the flying by the Allied Missions in the BCZ which

explains why there was no such reciprocal arrangement at Bunde. Because of this, our activities in the event of a forced landing in East German

territory would leave us completely isolated as there could be no immediate bargaining and the fate of Gary Powers, the U2 pilot shot down over the

Soviet Union in 1960, sprang frequently to mind. Fortunately, it never came to that as the 145hp Gypsy Major engine

proved more than equal to the task despite the fact that on at least two occasions bullet holes were discovered in the aircraft spinner.

On one of these occasions we had proof that a Soviet soldier had fired the shots as he had been photographed with his Kalashnikov pointing at the Chipmunk.

These incidents led to a bout of flying training for those who were not pilots in case of an unlucky shot hitting the pilot. At the time, as I was a

navigator, I was obliged to take part in this activity and was so successful that the Station QFI, Mike Neil, told me that if I ever managed to learn to

fly, he would take up studying the Russian language. Since gaining a private pilot's licence, I now realize that the Chipmunk is not the easiest of aircraft

to fly, but despite this Mike Neil has still not started his Russian course! We did however have contingency plans in case of engine failure, but as

anybody who has flown light aircraft knows, at 1,000 ft (or less) there is less than two minutes in which to select a landing area and in our case the added

problem of getting rid of incriminating evidence. We did not take too seriously the suggestion that we gather together all the cameras, lenses and

exposed films, pack them in a green bag carried for the purpose and drop them in the nearest convenient lake. Or, even less practically, try and stow

the bag in the space behind the pilot's seat, where I suspect that somebody might have found it with very little effort. Anyway as the photographer was

jammed in the front of the aircraft, there was very little room to do anything. With two camera bodies, two lenses, lots of spare films and a notebook it

was impossible to hide what we were doing. Particularly in an emergency when both crew members would be fully occupied in finding a suitable area

for a forced landing. Because of these problems of space and time before colliding with the ground, the contingency plan was that on coming to a

stop, the drain cocks under the wings would be opened and the aircraft set on fire with the mini-flares that we carried, before we were detained -

provided, of course, that we were still conscious.

On one of these occasions we had proof that a Soviet soldier had fired the shots as he had been photographed with his Kalashnikov pointing at the Chipmunk.

These incidents led to a bout of flying training for those who were not pilots in case of an unlucky shot hitting the pilot. At the time, as I was a

navigator, I was obliged to take part in this activity and was so successful that the Station QFI, Mike Neil, told me that if I ever managed to learn to

fly, he would take up studying the Russian language. Since gaining a private pilot's licence, I now realize that the Chipmunk is not the easiest of aircraft

to fly, but despite this Mike Neil has still not started his Russian course! We did however have contingency plans in case of engine failure, but as

anybody who has flown light aircraft knows, at 1,000 ft (or less) there is less than two minutes in which to select a landing area and in our case the added

problem of getting rid of incriminating evidence. We did not take too seriously the suggestion that we gather together all the cameras, lenses and

exposed films, pack them in a green bag carried for the purpose and drop them in the nearest convenient lake. Or, even less practically, try and stow

the bag in the space behind the pilot's seat, where I suspect that somebody might have found it with very little effort. Anyway as the photographer was

jammed in the front of the aircraft, there was very little room to do anything. With two camera bodies, two lenses, lots of spare films and a notebook it

was impossible to hide what we were doing. Particularly in an emergency when both crew members would be fully occupied in finding a suitable area

for a forced landing. Because of these problems of space and time before colliding with the ground, the contingency plan was that on coming to a

stop, the drain cocks under the wings would be opened and the aircraft set on fire with the mini-flares that we carried, before we were detained -

provided, of course, that we were still conscious.

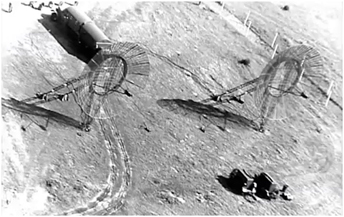

Véhicule de détection radar du champ de bataille SNAR-10 "Leopard" (chassis MT-LB). © BRIXMIS.

Véhicule de détection radar du champ de bataille SNAR-10 "Leopard" (chassis MT-LB). © BRIXMIS.

SNAR-10 "Leopard" battlefield radar vehicle (MT-LB chassis). © BRIXMIS.

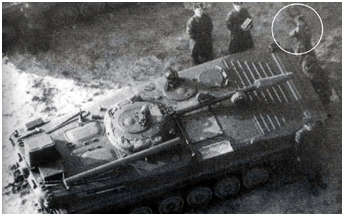

Véhicules 1V15 (chassis MT-LBU) destinés aux commandants de bataillons d'artillerie en cours d'entretien. © BRIXMIS.

Véhicules 1V15 (chassis MT-LBU) destinés aux commandants de bataillons d'artillerie en cours d'entretien. © BRIXMIS.

1V15 artillery battalion commander's vehicles being serviced (MT-LBU chassis). © BRIXMIS.

We were briefed to keep an eye out for certain items of equipment and

to look for unusual troop movements that might presage exercise activity or something more sinister. Instant recognition of Soviet Army equipment was

therefore essential in order to enable BRIXMIS to detect the introduction of new "kit". In this vein, one of our more spectacular finds was to discover

that the Soviets had sprayed up to 80 per cent of their equipment with anti infrared detection paint.

The sorties were normally between 1 hour 45 minutes and 2 hours 15 minutes but we were given a great deal of latitude in which installations we

photographed in the BCZ. The installations that lay within the zone included several major Soviet divisional headquarters, several ground

ranges, a Soviet reconnaissance base equipped with MiG-25 "Foxbat" aircraft [Werneuchen],

two helicopter bases [Oranienburg and Rangsdorf] and many other important but less prestigious

targets. Having been given permission to fly in the local area (not below 1,000ft), a normal sortie would start in the local Potsdam area to the west of

West Berlin, where there were three major Soviet divisions, 10th Guards Tank Division (at Krampnitz), 35th Motor Rifle Division (at Döberitz) and an important Frontal asset,

34th Artillery Division (at Potsdam), where they had the disturbing habit of training their guns on the aircraft as we flew around the installation. We would then

progress to the rail sidings that served these units and finally fly to their associated training areas. The reason for this concentrated effort was that we

would be able to report any activity to whoever was going to be on the ground in the Potsdam area for 24 hours on the local tour which all three

Allied Military Missions shared. Interesting activity was much more obvious from the air as it was more difficult to conceal, and of course it

would help the local ground tour to avoid trouble in areas where they could be easily detained such as rail sidings where there was every possibility of

being ambushed since there was often only a single track in and out to the railhead where equipment was unloaded.

My own preference, as the photographer, was to fly clockwise around the BCZ, although the other RAF officers had their own way of flying the zone.

|

Safety of Flight not Garanteed < Part 1 > Part 3 > Part 4 |

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |