In May 1958, a Belgian Air Force RF-84F was intercepted over the GDR and forced to land at the Soviet airfield at Damgarten. Daniel Brackx had the opportunity to question its pilot during the summer of 2011. Here is the text of that interview that sheds light on this unusual Cold War event.

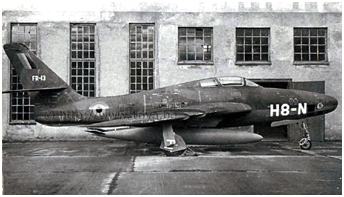

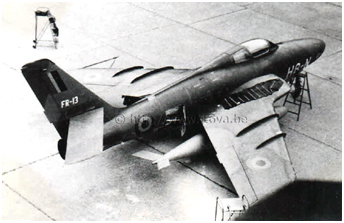

In the late afternoon of May 28, 1958, Second Lieutenant Martin Paulus of the 42nd Reconnaissance Squadron based at Brustem had just taken off for Kleine Brogel

in RF-84F "Thunderflash" FR-13 coded H8-N. It was a regular transit flight to reposition the aircraft because the next day he had to fly a mission to northern Europe

as part of an interception exercise called "Tempo Cativo" (this type of mission took place on a regular basis; exercise flights southward bore the code name "Tempo Bello").

For this mission, the Thunderflash was to fly at 20,000 feet to the Danish island of Bornholm located south of Sweden in the Baltic Sea. Danish and Norwegian fighters were

supposed to intercept the potential intruder.

As Martin recalls: «I had repositioned my RF-84F at Kleine Brogel, because the Brustem runway was too short to allow a safe takeoff with the full complement of fuel

planned for this long flight. On the morning of May 28, bus service from my Brustem home base had brought me to Kleine Brogel, where I had prepared my flight plan under

primitive conditions [the mission took place May 29]. The room contained no furniture and I had traced my navigation on the maps laid on the floor. Whether it was due to

the difficult conditions under which I had prepared my flight plan or because of the bad weather, the fact remains that I confused two German lakes, the Dümmersee

(30km NE of Osnabrück) and the Steinhuder Meer (at the same height, but further east, NW of Hannover), so I was flying about 65km further east than expected.

In the late afternoon of May 28, 1958, Second Lieutenant Martin Paulus of the 42nd Reconnaissance Squadron based at Brustem had just taken off for Kleine Brogel

in RF-84F "Thunderflash" FR-13 coded H8-N. It was a regular transit flight to reposition the aircraft because the next day he had to fly a mission to northern Europe

as part of an interception exercise called "Tempo Cativo" (this type of mission took place on a regular basis; exercise flights southward bore the code name "Tempo Bello").

For this mission, the Thunderflash was to fly at 20,000 feet to the Danish island of Bornholm located south of Sweden in the Baltic Sea. Danish and Norwegian fighters were

supposed to intercept the potential intruder.

As Martin recalls: «I had repositioned my RF-84F at Kleine Brogel, because the Brustem runway was too short to allow a safe takeoff with the full complement of fuel

planned for this long flight. On the morning of May 28, bus service from my Brustem home base had brought me to Kleine Brogel, where I had prepared my flight plan under

primitive conditions [the mission took place May 29]. The room contained no furniture and I had traced my navigation on the maps laid on the floor. Whether it was due to

the difficult conditions under which I had prepared my flight plan or because of the bad weather, the fact remains that I confused two German lakes, the Dümmersee

(30km NE of Osnabrück) and the Steinhuder Meer (at the same height, but further east, NW of Hannover), so I was flying about 65km further east than expected.

Not realizing that my position was too far east, for the first time I crossed the infamous "Iron Curtain" by overflying East Germany while en route to Bornholm. The interception

over Bornholm went according to plan, although I saw no fighters because their mission was accomplished by radar.

A few minutes after I had begun the return flight, seeing that I could not establish my position, I transmitted on 243.0 MHz UHF frequency in

accordance with the so called "Brass Monkey Recall Procedure," but my radio remained silent. This procedure was mentioned in the manual entitled "Military Information

Publication Germany" in which it was stipulated that this procedure should be followed in an emergency when a pilot was close to the "deconfliction line," that is to say,

near the border with East Germany. After ten minutes, I knew for sure that I was lost when suddenly I noticed a MiG-17 with large red stars on the fuselage and tail flying

alongside. The Soviet fighter then rocked its wings, an international signal meaning "follow me immediately."

Later, the Russians informed me that the interception had taken place over the city of Rostock. The idea of performing a "Split S" maneuver to escape the MiG briefly crossed my mind.

However, my experience and training made me realize that a second MiG was definitely behind me in the firing position, ready to fire its guns. So I was forced to follow

the Soviet aircraft. However, I extended the landing gear and flaps of the FR-13 while setting the throttle to 100% in order to burn maximum fuel, because I was still

too heavily loaded to land safely.

Not realizing that my position was too far east, for the first time I crossed the infamous "Iron Curtain" by overflying East Germany while en route to Bornholm. The interception

over Bornholm went according to plan, although I saw no fighters because their mission was accomplished by radar.

A few minutes after I had begun the return flight, seeing that I could not establish my position, I transmitted on 243.0 MHz UHF frequency in

accordance with the so called "Brass Monkey Recall Procedure," but my radio remained silent. This procedure was mentioned in the manual entitled "Military Information

Publication Germany" in which it was stipulated that this procedure should be followed in an emergency when a pilot was close to the "deconfliction line," that is to say,

near the border with East Germany. After ten minutes, I knew for sure that I was lost when suddenly I noticed a MiG-17 with large red stars on the fuselage and tail flying

alongside. The Soviet fighter then rocked its wings, an international signal meaning "follow me immediately."

Later, the Russians informed me that the interception had taken place over the city of Rostock. The idea of performing a "Split S" maneuver to escape the MiG briefly crossed my mind.

However, my experience and training made me realize that a second MiG was definitely behind me in the firing position, ready to fire its guns. So I was forced to follow

the Soviet aircraft. However, I extended the landing gear and flaps of the FR-13 while setting the throttle to 100% in order to burn maximum fuel, because I was still

too heavily loaded to land safely.

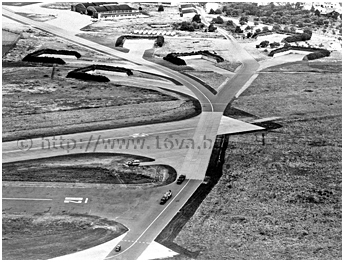

Once above the base from which the MiG came, I did a "break" to land, but seeing that the runway was very short (1),

I made a go-around because my aircraft was still too heavy to be able to stop in time. At that moment, the MiG fired a few salvos at me; I did not need a second warning.

I made a reasonably good landing using my drag chute.»

Then many people at the airfield came to see the enemy "fighter" that had arrived from the west. It was like a fun fair, Martin said. He was also "welcomed" by the base

commander and taken to a room where the commander and two other officers tried to question him. Martin continues: «My knowledge of the Russian language was nil and, with

their 'broken English,' we could not get very far. The second day, two majors who spoke good English came, but the interview did not go further than my name, my

identification number and my grade. That same day, I met the two pilots who had intercepted me and everything went in a friendly manner. At one point, they even pulled

out a map to show me exactly where the interception took place and how they had escorted me to Damgarten, an airbase located in northern East Germany.

Once above the base from which the MiG came, I did a "break" to land, but seeing that the runway was very short (1),

I made a go-around because my aircraft was still too heavy to be able to stop in time. At that moment, the MiG fired a few salvos at me; I did not need a second warning.

I made a reasonably good landing using my drag chute.»

Then many people at the airfield came to see the enemy "fighter" that had arrived from the west. It was like a fun fair, Martin said. He was also "welcomed" by the base

commander and taken to a room where the commander and two other officers tried to question him. Martin continues: «My knowledge of the Russian language was nil and, with

their 'broken English,' we could not get very far. The second day, two majors who spoke good English came, but the interview did not go further than my name, my

identification number and my grade. That same day, I met the two pilots who had intercepted me and everything went in a friendly manner. At one point, they even pulled

out a map to show me exactly where the interception took place and how they had escorted me to Damgarten, an airbase located in northern East Germany.

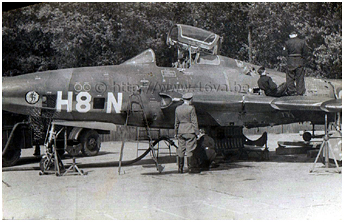

Le FR-13 à Damgarten quelques heures après son arrivée impromptue. © Collection Romualdovitch.

Le FR-13 à Damgarten quelques heures après son arrivée impromptue. © Collection Romualdovitch.

FR-13 at Damgarten, seen a few hours after its unexpected arrival. © Romualdovich Collection.

This friendly 'conversation' among pilots was abruptly interrupted by a senior officer who quickly swept the map away from under the nose of the pilots.

I spent one week at Damgarten Airbase, having by now learned its name. I stayed in two rooms and I could go up to the stairs where there was a guard. I did not

really feel like I was a prisoner. It is the ignorance of what was happening at home that weighed the most on my mind. My wife only had found out that I was still

alive after three days. The next two weeks were spent in a much stricter manner when I was transferred to the East German police, who locked me in a villa in a wooded area.

Although I was free to walk (no one had ever left the woods alive, I was told), I was constantly accompanied by a guard. The East Germans (were they from the Ministerium

für Staatssicherheit or Stasi?) tried for several days, with the help of a beer rack, cigarettes and a great many attempts at persuasion, to convert me to their cause so

that I could stay in the GDR.

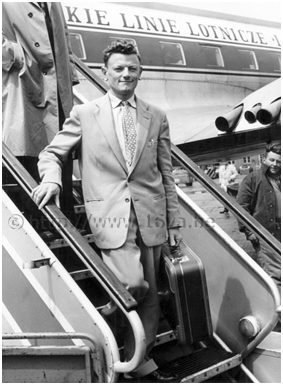

Until then, I always had worn my flight suit; however, one day I received civilian clothes much too large for me and, soon thereafter, three men

took me at 2.30 am to Berlin-Schönefeld Airport, SE of East Berlin. I later boarded an Il-14 belonging to the Polish airline LOT

(Polskie Linie Lotnicze) bound for Brussels, where I was greeted at Melsbroek Airfield (which at the time was still a civilian airfield) by the press,

generals Burniaux and Donnet, government officials and, first and foremost, my wife.»

The arrival of Lieutenant Martin Paulus at Melsbroek on 21 June aroused much interest from the press and this incident caused a stir in 1958, while the Cold War was in full swing.

Rumors circulating in the Air Force even referred to the personal intervention of Queen Elizabeth to release the pilot.

Until then, I always had worn my flight suit; however, one day I received civilian clothes much too large for me and, soon thereafter, three men

took me at 2.30 am to Berlin-Schönefeld Airport, SE of East Berlin. I later boarded an Il-14 belonging to the Polish airline LOT

(Polskie Linie Lotnicze) bound for Brussels, where I was greeted at Melsbroek Airfield (which at the time was still a civilian airfield) by the press,

generals Burniaux and Donnet, government officials and, first and foremost, my wife.»

The arrival of Lieutenant Martin Paulus at Melsbroek on 21 June aroused much interest from the press and this incident caused a stir in 1958, while the Cold War was in full swing.

Rumors circulating in the Air Force even referred to the personal intervention of Queen Elizabeth to release the pilot.

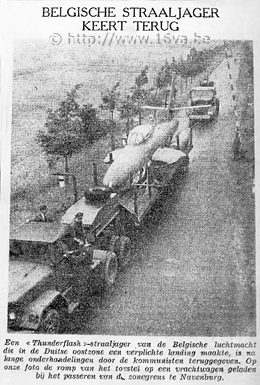

Coupure de journal montrant le FR-13 lors du passage de la frontière interallemande à Lauenburg

(et non pas à Navenburg comme il est mentionné sous la photo), à l'ouest de Hambourg. © Collection D.Brackx.

Coupure de journal montrant le FR-13 lors du passage de la frontière interallemande à Lauenburg

(et non pas à Navenburg comme il est mentionné sous la photo), à l'ouest de Hambourg. © Collection D.Brackx.

Newspaper clipping showing the crossing of the intra-german border by RF-84F FR-13 at Lauenburg

(and not Navenburg as mentioned in the picture caption), west of Hamburg. © D.Brackx Collection.

Martin Paulus lors de sa descente d'avion à Melsbroek. © Collection M.Paulus.

Martin Paulus lors de sa descente d'avion à Melsbroek. © Collection M.Paulus.

Martin Paulus upon his arrival at Melsbroek. © M.Paulus Collection.

After the happy ending of this grim adventure for Martin,

his Thunderflash FR-13 also was repatriated to Belgium on 30 June 1958, thanks to Joseph Leenaerts (who had participated in negotiations with the Soviets and East Germans to

release Martin Paulus) and technical officer Lieutenant Steurs, among others. The Air Force Staff initially wanted to send 19 men to Damgarten to dismantle the aircraft.

On June 27, Leenaerts and Steurs in a ZiM sedan reached Damgarten, where they found the RF-84F covered with tarpaulins. For the Soviets, the aircraft could have taken off,

but Joseph Leenaerts had been instructed to take it apart. The Thunderflash was dismantled June 29 and 30, apparently by East German personnel

(2). The question as to whose

trucks were used to transport it through the GDR remains open. The newspaper clipping illustrating this article shows that the fuselage on a trailer towed by a GMC truck crossed

the inner German border. Although the aircraft apparently seemed in good condition, those who had examined and dismantled it had caused plenty of damage, either through

negligence or due to the lack of appropriate tools. Thus, the access doors had been forced open and most of the lenses were broken. This episode necessitated a major

overhaul and structural repairs (IRAN) by Flight Refueling at Tarrant Rushton in the UK. But, the life of FR-13 was to be brief after its return to the 42nd Squadron

in late 1959. On May 17, 1960, the aircraft was irreparably damaged when it ran off the runway during a landing at Lahr, FRG, because of the blocking of the right wheel.

Captain Richir, who was flying it, fortunately escaped unharmed. The nose of the aircraft was recovered, later to be grafted onto FR-22.

On 6 September 1976, Viktor Belenko landed his MiG-25P at Hakodate in Japan. In early November of that year, a Belgian newspaper took the return of the MiG-25 to the USSR as pretext to publish an interview with Martin Paulus. Here is an excerpt that provides some additional details about his period of detention in the GDR.

«The whole airbase came to see me. A general took me in his car to drive me to his office for a first questioning in broken German.

It was quickly determined that I was simply lost. I was then confined in a villa on the outskirts of the airfield. I was interrogated every day and

I was playing billiards, cards or was watching television the rest of the time. The Colonel's wife was baking pies for me and provided me with cold dishes from their home.

When, after a week, I was transferred to the East German authorities, one of the officers' young daughter gave me a bouquet of flowers "because I had also

children and I was away from home." The Russians were friendly people. |

Translation of the second paragraph of the Belgian newspaper clip from June 1958 at left:

Translation of the second paragraph of the Belgian newspaper clip from June 1958 at left:

"BELGIAN PILOT PAULUS ALSO AT STRAUSBERG"

"According to [the information collected by] the Allied services [intelligence and/or Military Liaison Missions] in West Berlin,

the Belgian pilot Martin Paulus now would be detained at the East German People's Army Headquarters in Strausberg, 25 km from East Berlin.

This is also where the nine U.S. soldiers fell into the hands of the East German authorities on June 7 should be.

According to the West German newspaper "Der Abend," the Belgian pilot and the U.S. military would be correctly treated but would suffer long

interrogations"

At a press conference after his return to Belgium on Saturday June 21, Paulus said that he had been again interrogated by LSK/LV personnel on Friday,

which at first glance seems to corroborate the previous information. However, the testimony of Paulus in the box above is different: he was detained at

Rostock near Damgarten.

According to that newspaper, U.S. military would have been detained in Strausberg at the same time. They were crew and passengers of

a Sikorsky H-34 that was performing a liaison flight between

Frankfurt-am-Main and Grafenwöhr on June 7, 1958. It made an emergency landing (perhaps lost and out of fuel) because of bad weather conditions near Frankenberg

in the Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz) district. Eight officers (including a staff officer) and one sergeant from the 3rd U.S. Armored Division were aboard.

The Americans were actually detained in a villa at Dresden. They were released on July 19, 1958.

notes

(1) This appreciation concerning the runway length was very likely influenced by the stress level of the pilot and the unusually

high weight of an aircraft equipped with two additional tanks still containing fuel.

(2)

The known photographs of the RF-84F in the GDR illustrating this article show East German personnel

disassembling the aircraft.

The interview of Martin Paulus on which this article is based was published in the book that Daniel Brackx devoted to the RF-84F in service with the Belgian Air Force: "Republic RF-84F Thunderflash in dienst bij de Belgische Luchtmacht, Flash Aviation Shop."

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |