My first flying program

Gros plan sur le conteneur de type "N" d'un MiG-21R du 294.ORAP. Il s'agissait en l'occurence d'un modèle destiné à la reconnaissance

de nuit (caméras optiques et IR) comme le montrent les nombreux orifices d'éjection de cartouches éclairantes. Ces conteneurs disposaient également de lance-leurres dont

les orifices se trouvaient à l'arrière du pod. © USMLM.

Gros plan sur le conteneur de type "N" d'un MiG-21R du 294.ORAP. Il s'agissait en l'occurence d'un modèle destiné à la reconnaissance

de nuit (caméras optiques et IR) comme le montrent les nombreux orifices d'éjection de cartouches éclairantes. Ces conteneurs disposaient également de lance-leurres dont

les orifices se trouvaient à l'arrière du pod. © USMLM.

Close up on the type 'N' pod of a 294.ORAP MiG-21R. It was a night reconnaissance pod (optical and IR cameras), hence the numerous

lighting flare ejectors visible underneath. Self-defence flares could also be ejected from the rear of the pod. © USMLM.

Un MiG-21R équipé d'un conteneur de reconnaissance photo diurne de type "D" photographié lors d'une manifestation à Allstedt. © A.Ts.

Un MiG-21R équipé d'un conteneur de reconnaissance photo diurne de type "D" photographié lors d'une manifestation à Allstedt. © A.Ts.

A MiG-21R equipped with a daylight photo reconnaissande 'D' type pod during an event at Allstedt. © A.Ts.

As we departed the SA-3 site area, we noticed the Allstedt MiG-21R FISHBED H tactical reconnaissance aircraft were now active.

We dashed back to the airfield area and took up an OP in the landing pattern. This position was atop the Dummerberg, a high point 825 meters elevation above sea level not

far from the radar site, as indicated in the Google Earth photo on the previous page. The aircraft crews were making their turn onto their final approach for landing right above us,

giving us an excellent view of the aircraft, its side number and of the fuselage-mounted reconnaissance pod. We began to photograph each aircraft and note the side number and time

of landing. I was very excited, as this was the first flying program I had ever seen.

Some time passed as Lynn and I continued shooting pictures and logging data. Since the reconnaissance tour NCO was responsible for security in an OP, Nick was being watchful.

He suddenly announced that we had company. The narks had found us, perhaps as a result of a report from that irate VOPO? Our OP was in the middle of a huge field from which

hay recently had been cut. The surface of the field was dry and hard so there was no way this one vehicle carrying a couple of narks was going to

give us much trouble. Being such a novice, I was quite concerned, but Lynn’s reaction was to ignore them: “We have plenty of room to run. It will take a small army of

narks to block us in and catch us.”

So, we did just that - we ignored them until we noticed that several more vehicles had gathered in various parts of this large field. The narks were forming some sort

of attack force to try and detain us. As they begin to deploy, Lynn decided it was best to leave the area. We had gotten good coverage of the flying program, and it was time to depart.

A lesson learned

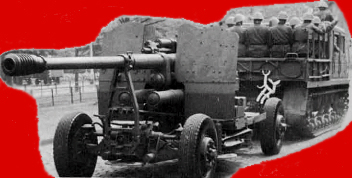

Un canon KS-19 de la NVA lors d'un défilé à Berlin-Est.

Un canon KS-19 de la NVA lors d'un défilé à Berlin-Est.

A NVA KS-19 gun on parade in East Berlin.

After we were chased away from our Allstedt OP, our three-man reconnaissance tour team headed for the vicinity of our next day’s target, Grossenhain Soviet Airfield 90 miles away.

Lynn decided to check to see if there was any flying going on in the Köthen Soviet Airfield vicinity, which was on our

route east to Grossenhain. There was no activity there so Lynn decided to check a nearby Soviet anti-aircraft artillery unit equipped with the KS-19 100mm gun.

This unit was located on the edge of the city of Köthen and difficult to approach not only due to traffic congestion, but because the Permanent Restricted Area

boundary impinged our movements.

Nonetheless, we worked our way quite close into the target. Lynn passed me his camera so I could load a fresh roll of film for him.

As I handed the camera back to him, we observed gun crew drills in progress. Lynn told Nick to drive in close to the activity. Nick headed at high speed toward the activity

and slid the car to a stop with the vehicle sideways to give Lynn a good view. The only sounds heard were my rapid breathing and the whir of the Nikon F motor drive.

Lynn shot up the activity and we beat a hasty retreat.

As we exited the area, Lynn handed the camera back to me and asked me to remove the exposed film and repeat the loading process. I pressed the release, awaiting the

familiar sound of the film being rewound. Alas, no familiar sound was heard. I tried again, with the same lack of results. It turned out I

had improperly loaded the camera the first time so the film did not advance while Lynn was filming the gun crew in action. We had sensitized the target, of course,

so we could not go back and try again.

A bit later, Lynn took me aside for a short heart-to-heart chat. He instructed me on the correct film-loading procedure. “You must manually turn the take-up reel

to ensure the film is tight and then burn off a frame or two. While doing this, you must watch the feed reel to see that it actually is turning and the

take-up reel is taking up the film.” Fortunately, the KS-19 was not a new weapons system and we really did not lose any valuable information. Thus, a good lesson was

learned at virtually no cost, other than my chagrin and embarrassment. After this debacle, we began our search for a safe place to sleep in the woods close to Grossenhain Airfield.

We performed some circuitous routing

to ensure we were not being closely surveilled and found a suitable wooded location. The next morning we made our way carefully to a preliminary observation point near the airfield

and awaited activity. Unfortunately, no flying activity ensued so we "closed up shop" and made our way back to the Potsdam House.

Personal collection problem

Following my on-the-job training, I was deemed proficient enough to run collection missions alone.

As was the normal procedure, my breaking-in period after the OJT was structured such that I was not assigned highly sensitive targets right away. However,

covering flying programs was not terribly risky if all security procedures were followed and the tour team remained on guard and observant.

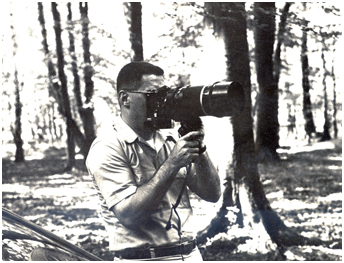

As time passed, it became clear that I had a personal problem. I simply was unable to get objects in proper focus using the Soviet MTO-1000mm lens shown right, the Maksutov

Teleob”ektiv that won Grand Prix at the World Fair in Brussels in 1958 . This was the first 1000mm mirror lens in the world.

This lens was extremely difficult to use. It was bulky and very heavy, weighing 8.7 pounds. One really had to practice in order to learn how to keep a moving aircraft in focus.

Things finally reached such a state that Lieutenant Colonel Dave Colgan, the Air Team chief, called me in one day in the early

spring of 1972. He informed me that he had made an appointment with the eye doctor for me. Perhaps all I needed was new glasses? The tests showed that my glasses were fine

and my vision was 20-20 corrected. The problem lay elsewhere.

Technical Sergeant Nick Netter and I discussed this subject at length and he came up with the solution. “I know what your problem is! You are too far away from the targets.

I will make sure you get closer so you can focus correctly.” From that moment on, my personal problem disappeared. At the same time, my collection efforts improved tremendously,

as did my confidence in my ability to do the job. Addition of the Nikon 1000mm lens to the Air Team equipment inventory later that year was an

extremely important element in the elimination of my personal problem...

As time progressed, my reconnaissance tour team partners and I often pushed the rules to get very close to our intended targets and, when the information to be collected was

of sufficient importance, we even broke the rules... However, we never became reckless and foolhardy. We certainly did become

more daring and resourceful and our subsequent results were prima facie evidence of that fact.

Following my on-the-job training, I was deemed proficient enough to run collection missions alone.

As was the normal procedure, my breaking-in period after the OJT was structured such that I was not assigned highly sensitive targets right away. However,

covering flying programs was not terribly risky if all security procedures were followed and the tour team remained on guard and observant.

As time passed, it became clear that I had a personal problem. I simply was unable to get objects in proper focus using the Soviet MTO-1000mm lens shown right, the Maksutov

Teleob”ektiv that won Grand Prix at the World Fair in Brussels in 1958 . This was the first 1000mm mirror lens in the world.

This lens was extremely difficult to use. It was bulky and very heavy, weighing 8.7 pounds. One really had to practice in order to learn how to keep a moving aircraft in focus.

Things finally reached such a state that Lieutenant Colonel Dave Colgan, the Air Team chief, called me in one day in the early

spring of 1972. He informed me that he had made an appointment with the eye doctor for me. Perhaps all I needed was new glasses? The tests showed that my glasses were fine

and my vision was 20-20 corrected. The problem lay elsewhere.

Technical Sergeant Nick Netter and I discussed this subject at length and he came up with the solution. “I know what your problem is! You are too far away from the targets.

I will make sure you get closer so you can focus correctly.” From that moment on, my personal problem disappeared. At the same time, my collection efforts improved tremendously,

as did my confidence in my ability to do the job. Addition of the Nikon 1000mm lens to the Air Team equipment inventory later that year was an

extremely important element in the elimination of my personal problem...

As time progressed, my reconnaissance tour team partners and I often pushed the rules to get very close to our intended targets and, when the information to be collected was

of sufficient importance, we even broke the rules... However, we never became reckless and foolhardy. We certainly did become

more daring and resourceful and our subsequent results were prima facie evidence of that fact.

|

My first back-seat tour < Part 1 |

|

Plan du site - Sitemap |  |